Gymshark part 2: co-founder exits, billionaire tax planning, securing the bag, and cash crunches

The rest of the Gymshark story, and where next from here?

Hello to the 97 new subscribers, joining our happy family of 1,764 business nerds for this week’s helping of P&L paradise. I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO and writer here in the UK, who one reader described as “the British Matt Levine?”, which I will keep quoting, without the question mark, until the day I die.

Last week’s deep dive was a beastly 3,000 words about rocket-ship apparel business Gymshark, and the behind-the-scenes boardroom shenanigans along the way to reaching £500m/yr in revenue. This week, we’re back with — unebelievably — another 4,000 words on the topic, because Gymshark’s story is both educational and wonderfully salacious gossip.

As always: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

Last week we looked at Gymshark’s blitzscale journey from a bedroom in Birmingham to a £500m/yr company.

As a recap, here’s Gymshark’s revenue since 2015. It’s a pretty stunning trajectory.

And I dove into the Companies House filings to try and figure out what happened between Gymshark’s two co-founders, Lewis Morgan and Ben Francis, and why Morgan left the business in 2016.

And yes, I may have indulged in some minor libel and slander, as I insinuated that now-CEO Ben Francis deliberately and ruthlessly tried to cut out his co-founder to end up with a bigger piece of a rapidly growing pie. Look at him — he does look ruthless.

And maybe that ruthlessness is the difference between, as Jason Calacanis would say, a billionaire and a centimillionaire.

But this week we look at the other side of the story, and consider:

why maybe it’s right to kick out a co-founder;

how Ben Francis has made several hugely important decisions to help Gymshark along;

and how Gymshark has financed its rapid growth in the famously cash-hungry world of inventory-based businesses.

Reminder: I put hours of research into these posts, and distil it down for your consumption. If you want more, you can grab the Excel model and charts I used in this post in the Net Income store:

You’ll be emailed the file as soon as you check out.

We’ll start with co-founder disputes.

Maybe it’s right to kick a co-founder out

This is how Ben described the co-founder split on the Diary of a CEO podcast:

There came a point where I had my vision, and I think [Lewis] had his vision. And I just want to be clear, I don't think one is better than the other. It was just a difference of opinion. And to be fair to him, he had so many other interests in terms of investments and property and all these different things. So Lewis essentially left…

To me, that sounds reasonable. Differences of opinion between co-founders or early-stage employees do happen. A lot. And not just between, say, Mark Zuckerberg and the Winklevoss twins, or Mark Zuckerberg and Eduaro Saverin, or Mark Zuckerberg and literally anyone else he’s ever come into contact with.

In fact, one of my favourite companies, Tiny, buys internet businesses all the time, and co-founder buyout is one of their main sources of dealflow:

Ben and Lewis were just 19 when they founded Gymshark, in 2012. By 2015, they’d had some success, and had some money in their pocket too. In their shoes, I’d think I could do anything I set my mind to.

So maybe Lewis did just have other interests that he wanted to pursue.

For example, on his LinkedIn page, right under Gymshark, Lewis mentions founding Maniere De Voir in 2013, just a year after Gymshark was launched:

Maniere De Voir is more fashion than gymwear, but still, it's an apparel ecommerce business, just like Gymshark.

So it's not, like, out of the realm of possibility that Lewis being involved in Maniere De Voir would create a conflict of interest with Gymshark.

Or not even a conflict of interest, but just a distraction. When you’re growing at the rate Gymshark was back then, you need all hands on deck just to keep the ship going in the right direction. I can see why if I was focusing on one business, and my co-founder — with an equal stake — was focusing on another, I’d be getting frustrated.

But that’s not quite the whole story.

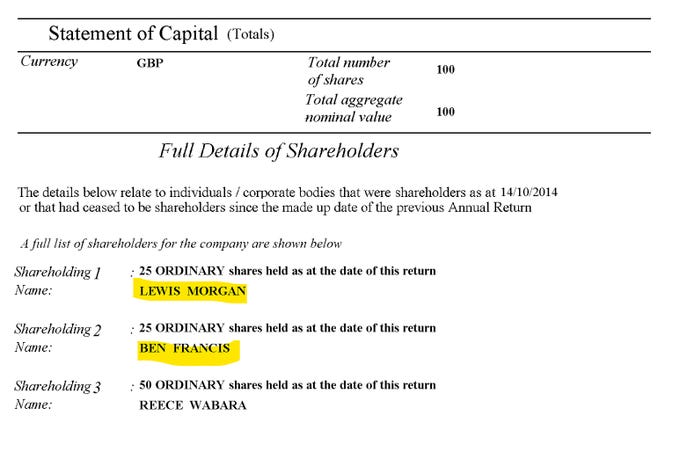

Intriguingly, if we look at the initial statement of capital for Maniere De Voir, back in 2013, Morgan and Francis were each 25% shareholders. Reece Wabara, who was playing professional football for Doncaster Rovers at the time, held the other 50%.

Maniere De Voir started trading, and did well. Not stunningly well like Gymshark, but well enough to keep going.

A couple of years later, in 2016, Lewis Morgan leaves Gymshark, in what sounds like acrimonious circumstances. As I highlighted last week, Lewis describes the split very differently to how Ben does:

“He [Ben] wants to say we had different visions — if he wants to clear his own conscience by making himself believe that, then so be it…

There’s a lot of skeletons in the closet that’ll never be spoken about because of contractual reasons…

Loads of nasty stuff went on behind closed doors though.”

But despite that nasty split, the pair remained partners in Maniere De Voir until 2018, at which point Ben either gave up his shares, or sold them to Reece Wabara — a full two years after Lewis has left Gymshark:

And Maniere De Voir today is a wonderful company, doing over £30m in revenue, nearly £3m in net profit, with a total of £7.3m in retained earnings.

It’s no Gymshark, of course, but it’s a thriving small business. Over time Lewis has given more shares to Reece Wabara, so the business is now 83% owned by Wabara, and the remaining 17% by Lewis Morgan:

All this to say: yes, it looks perfectly plausible that both Lewis Morgan AND Ben Francis had other business interests when Morgan left Gymshark.

Which means we have one potential explanation for what happened — but remember, I have zero insider knowledge or information, so this is all wild speculation to take with a pinch of salt.

The way Ben tells it, all the following things happened at roughly the same time in 2015:

Lewis left the business due to differing visions

Ben meets Paul Richardson, former All Saints investor and director, at the gym

Richardson introduces Ben to Steve Hewitt, a former Reebok exec

Ben receives some 360 feedback from his leadership team that makes his realise he’s not the right person to lead Gymshark on its next growth phase

Ben asks Richardson to join Gymshark as Exec Chairman, and Hewitt becomes CEO.

That’s how, as we discussed last week, we ended up with Hewitt taking 5% of the company in October 2015:

That’s the version Ben tells for public consumption.

A different interpretation of this story might be:

Ben and Lewis are young, naive, somewhat distracted, 20-somethings full of ego and some money, and have a rocket ship business on their hands. They think they can do anything, and start creating other businesses like Maniere De Voir.

The pair then meet experienced businessmen Paul Richardson and Steve Hewitt, who tell them words to the effect of:

“What the fuck are you doing? Gymshark's the golden goose, just don't get distracted or fuck it up and you’ll both be rich — and we can help you.”

And maybe Ben takes that message to heart — and Lewis doesn’t.

Ben goes all-in on Gymshark, wholeheartedly, and swears to spend the next decade building an amazing company. Lewis wants to keep building other businesses too, and investing in property, and generally being a big swinging dick.

So between them, Ben, Steve Hewitt, and Paul Richardson realise they need to tackle that problem now, rather than later.

Because if you've got a founder with a big stake in the business, who's no longer engaged, no longer pulling their weight, and racking up conflicts of interest left, right, and centre, that's a big problem. It needs to be dealt with as soon as possible, before the company gets too valuable, and dealing with the problem becomes too expensive.

This is where we have to give Ben Francis a ton of credit.

Driven by a singular vision to create an iconic British brand to rival Nike and Lululemon.

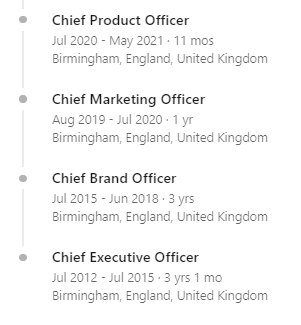

Smart enough and self-aware enough, even in his early 20s, to realise that he should bring on outside help, and step down as CEO.

Humble enough to then spend 6 years in different roles, learning at the right hand of more experienced team members, before taking up the CEO mantle again in 2021:

I’ve spoken to a couple of people who know a bit about Gymshark, and the one thing they both mentioned was this:

Ben Francis didn’t really know what he was doing. He didn’t have a clue how to actually run a business. But he knew enough to find the right people.

Which is the entrepreneur’s job! That’s what entrepreneurship is: assembling the team, the resources, setting the vision, and driving the company forward towards that vision. It’s a classic story of who, not how.

So driven by that vision, Ben did what he needed to do and removed the obstacle that could prevent Gymshark from becoming the company he knew it could:

and in exchange, he agreed to forfeit, or sell, his shares in Maniere De Voir in 2018:

at which point the two co-founders go their separate ways, both wealthy men.

One, the relentless, focused, billionaire CEO of Gymshark.

The other, a mere centimillionaire, investor, property magnate, and plenty more besides.

Just different visions. But look at this chart:

Looking at that, it’s hard to say that Ben made any wrong decisions, or that Lewis was hard done by — remember, he sold half his stake at the 2016 valuation, and the other half at the 2020 valuation, for a rumoured $200m.

Billionaire-level tax planning

I’m starting to tire of fawning over two guys who are both younger, more ripped, and significantly richer than me, so we’ll round off with a couple of other interesting things I found out in my research that didn’t quite fit into the story we just told.

Firstly, Ben Francis has excellent tax advisors.

I shared some of my research with a friend of mine who’s had some business success. In particular, she saw the shareholdings, with half of Ben’s stake held via Francis Family Office Ltd and saw something I didn’t:

Francis Family Office Ltd isn’t a mere holding company, it’s a family investment company:

A Family Investment Company (FIC) is a bespoke vehicle which can be used as an alternative to a family trust. It is a private company whose shareholders are family members. A FIC enables parents to retain control over assets whilst accumulating wealth in a tax efficient manner and facilitating future succession planning.

The tax experts in the audience can correct me, but I believe this means:

Francis can gift shares in the FIC to his children now;

Those shares become more valuable over time as Gymshark distributes dividends to the FIC, which the FIC does not pay tax on;

FIC invests those distributed dividends in other assets over time, increasing the value of the shares he gifted to his kids;

Assuming Francis survives for seven years after donating those shares, they become exempt from inheritance tax.

A wonderful bit of tax planning. The sort of thing I won’t bother doing unless this newsletter really takes off, but I like to know about anyway.

To top it off, there’s a nice human interest story in Gloucestershire Live about him buying a farm in the Cotswolds for his family:

which sounds just lovely. So idyllic. Ben and his wife being the Gen Z influencers they are, they even released an announcement video about it.

Is this just a case of a family wanting some space to retreat to in order to get away from the hustle and bustle of daily life?

No! It’s a tax thing.

Buying a farm means you benefit from Agricultural Property Relief.

Which again, means that when Francis dies and passes on the family farm to his kids, they won’t pay inheritance tax.

Just remember that tax strategy every time you see a rich guy who, for some reason, owns a farm, despite having no farming knowledge, ability, or desire.

Or maybe they just want the farm to use as a set for a tremendously popular Amazon Prime show, I don’t know.

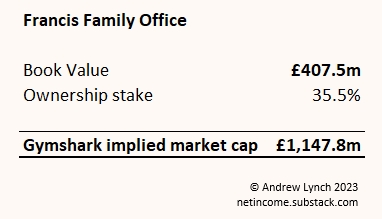

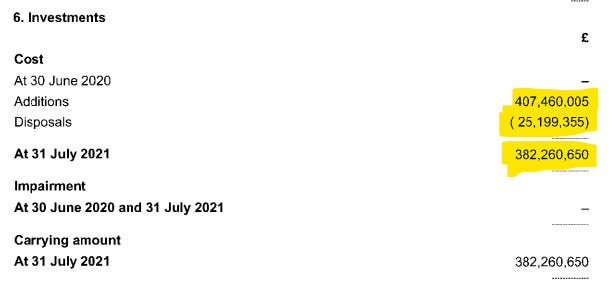

Lastly it’s worth pointing out that Francis Family Office Ltd took a big chunk of Ben’s shares as part of General Atlantic’s investment in 2020, valuing their 35.5% of the company at £407.5m (implying an overall Gymshark valuation of £1.15bn):

But between June 2020 and July 2021 they sold off £25.2m of that stake:

Meaning that Ben Francis has very much secured the bag.

Gymshark could go to zero tomorrow, and he’ll still be a rich man. Not billionaire rich, or even centimillionaire rich, but he’ll have enough to retire to his (tax-efficient) Cotswolds farm and live out his days in peace.

Managing cash in a growing business

I say this as someone who works in an inventory-based business: managing cash flow is brutal, especially when you’re growing rapidly.

Every penny you get from customers ends up being reinvested into more inventory. Cash is often the key constraint on how quickly you can grow — imagine a scenario where you could sell 100,000 gym t-shirts next month, but you’ve only got the cash to pay for 50,000. Well, that means you can only buy 50,000, which means you can only sell 50,000. Once you’ve collected the cash from those sales, you can buy more t-shirts.

The time it takes to turn money spent with your supplier into money in your own bank account is called your cash conversion cycle.

Cash conversion cycle =

Inventory days + Receivables Days - Payables Days

Managing this cycle is one of the most important parts of running an inventory business.

The perfect scenario would be getting credit terms from your supplier, buy the whole 100,000 t-shirts, sell them all, collect the money, and then finally pay the supplier. If you can get paid before you have to pay for things, that’s a negative cash conversion cycle, and it means your customers are funding your growth.

That’s what Gymshark was doing back in the day. This article, rather unimaginatively, is called How Gymshark used negative cash conversion cycles to build a billion-dollar business, and suggests Gymshark had a cash conversion cycle of minus 36 days:

This writer claims these figures come from Gymshark’s financial statements. So, following in the footsteps of former US president Ronald Reagan, I adopted the mantra of “trust but verify,” I decided to dig into the numbers myself.

I couldn’t match up these numbers exactly, but I got close to the overall number using the figures from Gymshark’s 2016 financials:

Looking at the 2016 figures, Gymshark was being paid on average 3.1 days after it sold the goods — which makes sense, it’s a DTC business, so customers are paying by credit or debit card at point of sale. No credit risk there (and my guess is the 3 days is the approx. time it takes the cash to clear from the card processor into Gymshark’s bank account).

More importantly, Gymshark looks to be holding inventory for only 81.6 days, and paying for it after 122.2 days — meaning that when they sell the inventory, they have another 40 days before they need to pay the supplier.

Wonderful! A negative cash conversion cycle, right?

Well, things have changed.

Since then, Gymshark’s cash conversion cycle has gotten continually longer and longer, every year. It’s now at 102 days.

Now, that might down to a couple of things:

International expansion, and dealing with a global supply chain

A deliberate choice to make sure they keep up with sales growth

Stockpiling inventory to make sure they never run out

Or, it could be that they’re just getting less and less efficient as a business. I don’t know.

So if they’re not funding their growth through a negative cash conversion cycle, and they only recently took outside money, how did they fund their growth?

Debt.

In the UK, when a company takes out a secured line of credit with a bank, it goes on Companies House as a registered charge. It’s so other lenders can credit check a company and see what assets are already pledged as security against other loans.

Here is a list of all the charges for Gymshark’s different entities:

Going back as far as 2015, they’ve taken out debt to fund growth. That’s fine — the company is profitable, and hasn’t had a problem servicing this debt. No doubt it comes with various conditions, covenants, and more, but for now, Gymshark hasn’t had any issues meeting those covenants.

That’s good, because if for whatever reason they fell into trouble, HSBC could take the keys to the kingdom.

As a reminder, this is Gymshark’s corporate structure:

And against its line of credit, Gymshark Group has pledged 100% of its shares of Gymshark Holdings as security. Gymshark Holdings has also pledged 100% of its shares of Gymshark Ltd.

Here’s the schedule from the registration of charge:

Now, that’s not necessarily an issue — as long as Gymshark can keep servicing the line of credit and meet its covenants. But this is a £50m line of credit we’re talking about, and they’ve drawn down every penny of it:

And their net borrowing increased by — you guessed it — nearly £50m in their last financial year:

They needed that money to finance the £49m increase in inventory in the year, which, along with some unfavourable exchange rate movements, is the main reason their cash flow from operating activities was negative £32m:

Again, none of this is necessarily an issue as long as the company is able to service the debt and meet its covenants.

On the face of it, Gymshark still has plenty of working capital to service the debt:

But its cash conversion cycle is getting longer and longer. In particular, Gymshark has a lot of cash tied up in inventory. If we exclude inventory from the working capital calculation, things look a lot worse:

Ouch. That’s why the debt is needed, to finance that negative working capital.

But as long as sales keep coming in, things will be fine.

On to the final piece of the puzzle.

Has Gymshark peaked?

Gymshark’s growth is certainly slowing. Here’s their year-over-year revenue growth since 2016:

You could argue that this is just an issue of scale — there are only so many people that want fancy workout gear, right? But remember last week we compared Gymshark to other brands in its category.

Lululemon is 13x the size of Gymshark, doing $8bn in annual revenue, and still growing at a faster rate:

We can also dive into some of the commentary in Gymshark’s financials to learn more.

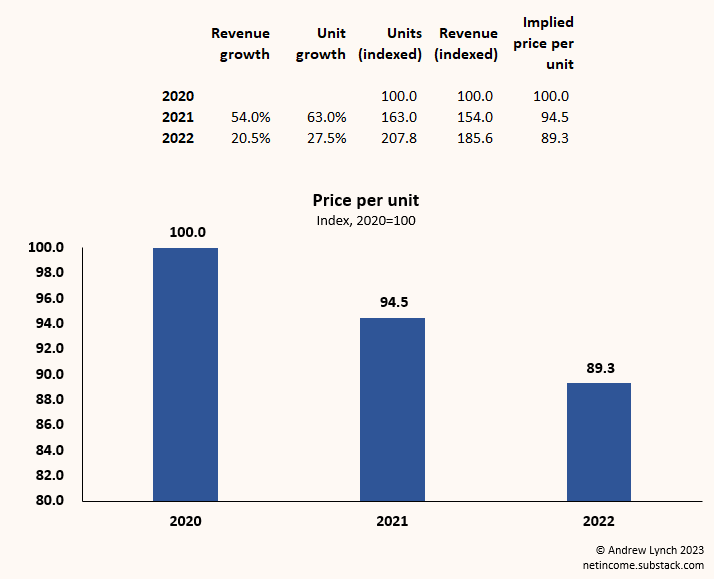

Firstly, they disclose that units sold grew by 27.5% in the year, and 63% in 2021:

but remember, revenue only grew by 20.5% in 2022, and 54% in 2021.

So if unit growth is outstripping revenue growth, that means the average selling price per unit sold is dropping.

In fact, in the last two years, the average selling price per unit is down 10.7%:

A bunch of Gymshark’s sales are international and priced in USD, so that price decrease might just reflect adverse exchange rate movements. It could also be a deliberate strategy as they increase their unit volume with suppliers, driving down their buying price, and passing the savings on to their customers.

Overlaying Gymshark’s gross margin onto this average price per unit tells us it’s a bit of passing on savings, and a bit of margin compression too. Between 2020 and 2022, average sales price per unit is down 10.7% , and gross margin has dropped by only 4.0%, implying that the other 6.7% is cost savings passed on to customers:

Not too bad then.

The only other worry is that the drop in selling price per unit, and the fall in gross margin, coincides with the big increase in inventory.

The concern here is that sales are slowing, inventory is accumulating, and Gymshark is having to discount to get rid of that inventory, possibly in order to meet debt covenants or solve cash flow issues.

This possible cash crunch is coming at the exact time that Gymshark are expanding into retail and wholesale — albeit only tentatively for now — which will both a) increase their receivables days, making their cash conversion cycle longer; and b) decrease their gross margins.

In their 2022 financials, Gymshark also hint at the revenue trajectory for 2023 year to date:

“Revenue is tracking at the same level as for the corresponding period.”

In other words, revenue hasn’t grown at all this financial year.

What does that mean for inventory levels? Cashflow? Ability to meet debt covenants?

No idea. But it looks like the stakes are higher than ever, and I’ll be watching closely to see how the company performs this year.

Of course, in the unlikely scenario that Gymshark runs out of cash, can’t meet its obligations, and HSBC take the keys, the co-founders will be just fine.

Remember Ben Francis has already sold off about £25m of his stake, and invested in his tax-efficient farm, among other things. Hence why he probably sleeps OK at night, and has a beaming smile.

The irony in that situation is that Lewis Morgan would have sold off his remaining 20% in 2020, at the absolute peak of the company’s growth trajectory and zero-interest-rate based valuation. He’d have played an absolute blinder.

Maybe being kicked out of Gymshark would be the best thing that ever happened to him.

The story isn’t over yet. I’ll report back when the next financials are filed, which will be… April 2024.

Stay on the edge of your seat until then, OK?

Carve outs

This Gymshark thing ended up being a ridiculously large amount of work over the last couple of weeks, so only one carve out this time. If you’re a fan of Net Income, you’ll undoubtedly enjoy this fantastic interview with Jeremy Giffon on Invest Like The Best. Jeremy was the first employee and General Partner at the aforementioned Tiny, and has a ton of experience buying and selling wonderful internet businesses. A fascinating discussion that covers topics like:

Esoteric opportunities that exist in private markets

How misaligned incentives and coordination problems create special situations for people like Jeremy to invest in

Compensation advice for CEOs

Meeting your heroes

and much more. Highly recommend it. Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts.

Support Net Income

As a reminder, you can support Net Income by visiting the Net Income store on Shopify to grab any of the models or slides used in this post, and other posts.

You can also click here to become a founding member of Net Income. Your support means a ton to me, and by signing up, you’ll get a host of other benefits, including first-look (and free) access to future courses, a monthly catch-up call with me, and access to the Net Income community.

Thanks. Until next week,

Andrew

Just finished both articles and got to say, really well done!

Not everything is as glamorous as it seems on a surface level. Nonetheless we got to acknowledge that we would likely do similar things if we were in ben's position. We want to believe that he bought a farm for his family out of purely self-less motivation. The reality is not everything is as ferry tale like as we would want it to be. Some things just make sense if you have such a high profile standing.

Not to justify demeaning or unlawful behaviour but often we're no better. I'm taking neither side here.

Thanks for writing Andrew!

just as good as part 1, thank you for writing these Andrew!