Hello! Welcome to Net Income, a behind-the-scenes look at some of the most interesting companies I find. I’m Andrew Lynch, a small company Finance Director here in the UK. If you’re getting this in your inbox, you’re one of the first 12 wonderful people to subscribe. Thanks, I appreciate it — and if you like this, please share it.

Without further ado, here’s a story about an SME I worked for a couple of years ago.

EDIT (28-Aug-24): more than a year after I started this newsletter, we’ve now got over 3,000 incredible subscribers. I’m blown away that so many people want to read what I have to say about small company financial statements, but it warms my heart to know there are thousands of us. Thank you. Without further ado, here’s the post.

A million pounds in profit.

After tax.

A lot of people are looking for a quick way to get rich. One weird trick or a hot stock tip that’ll set them up for life. Buying options on Gamestop at the right time. Bitcoin. An AI chatbot. A viral online course.

This is not that. This is a story about how you can take an OK business, in a difficult industry, and use it to create wealth for yourself, and for your team. If you’ve ever come across Nick Huber, aka @SweatyStartup on Twitter, you’ll know the kind of business I’m talking about.

This is a story about doing simple shit well, and generating millions of pounds of wealth as a result.

Background

For three years I had the pleasure of working in the finance department of a small business here in the UK.

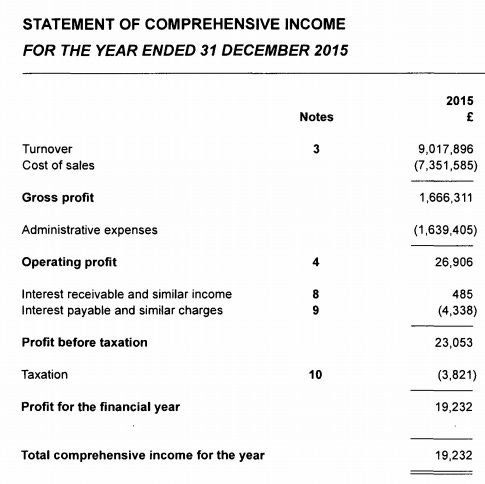

Here’s a screenshot of the P&L from 2015, the year before I joined.

£9M in revenue, and £19k in profit after tax. A great big meh.

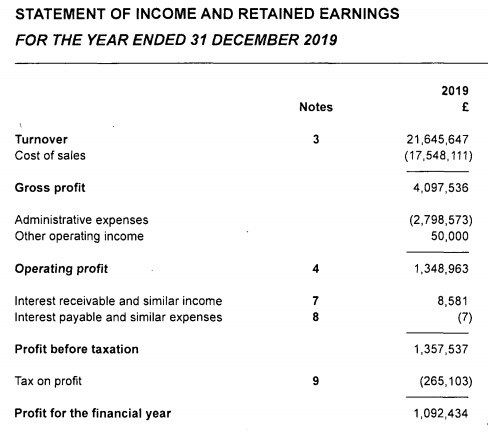

Here’s a screenshot of the P&L for 2019, the year I left:

£21.6M in revenue

£1.1M in profit after tax

Not a bad improvement.

(By the way, this is a UK company, so all of these numbers are completely public at Companies House. I’ve taken the liberty of putting them into some handy charts below).

There was no magic bullet here. No transformational change. And no single stroke of luck. Just a lot of hard work by a lot of people, and some financial discipline.

Here’s how we did it.

What was the company?

The company was a boutique facilities management company. They provided cleaning, security, reception, and maintenance services to companies across the UK. These are typically done on 3-5 year fixed price contracts.

Facilities management is a business with razor-thin margins. To get business, you need to bid for it. Bids are typically done on a cost-plus basis: you figure out how much it’ll cost you to deliver what the client wants, you add on a margin for overhead and profit, and that’s the price you bid.

Your competitors will be doing the same, driving margins down for everyone. Not every customer goes for the lowest bidder, though -- some are willing to pay extra for good service or a company they like -- but there’s only so much you can push on price.

So it’s hard to win a contract but, if you do, you lock in a certain amount of profit for 3-5 years, assuming you can deliver the services within budget.

On top of that, your clients may ask for extra services outside the scope of your fixed price contract, which you can provide to them, again on a cost-plus basis.

That means the game is:

Running your contracts efficiently

Getting extra income from clients where you can

Managing overheads

Winning more contracts

In a nutshell, this is just good old-fashioned financial discipline. So that’s what we did.

There were four key steps to get there:

Report accurate financials

Cut out leakage in both cost and revenue

Create reasonable, bottom-up budgets

Put together reasonable, well-costed bids to win more contracts

Step 1: Reporting accurate financials

When I first joined, our financials were a mess. Although payroll and billing were pretty accurate, accounts payable was metaphorically and literally all over the place: invoices in drawers, invoices with no purchase orders, invoices being posted in the mail to people to physically sign, invoices for things no one recognised.

Basically, we didn’t know what our costs were, or what they should have been, at any time. And because we didn’t have an accurate picture of the current state, we couldn’t say whether we were truly doing better or worse than the month before, or what a steady state month was, which made it impossible to budget and forecast accurately.

So, to fix this, we:

Put all the unpaid invoices on a spreadsheet

Sent out that spreadsheet to all the contract managers

Followed up relentlessly with contract managers to tell us what should be paid and what shouldn’t

That eventually cleared the backlog. Next, we put in these processes:

We refused to pay any supplier invoice that didn’t have a purchase order (PO) number quoted. Our suppliers quickly learned that they needed to push our contract managers to give them a PO before they supplied us with any goods or services.

We created a PO request form for our contract managers, which had the primary benefit of making sure the PO was coded correctly in our system, so the costs would end up in the right place, and we could track the financials accurately.

I created and automated a suite of reporting dashboards for each one of our contracts. That meant we could track, line by line, what costs we were incurring on every contract, and check all the variances, in detail, every month.

This all took about 4-6 months. By the end of that time period we were confident that we were accurately tracking our financial performance, across all of our contracts.

Step 2: Cut out leakage

In any business there is leakage. There are things you should be getting paid for, but you’re not. And there are things you’re paying for that you shouldn’t be.

We had both problems.

Our contract structure meant that certain work was in scope of the contract, and covered under the fixed fee. Other work would be outside of that and charged to the client ad hoc.

As an example, imagine you have a contract to clean someone’s office three times a week. The fixed price contract might cover the staffing costs and quarterly deep cleans of carpets and windows. Outside of that would be any cleaning equipment and materials like soap, toilet roll, mops, bucket, rubber gloves, and so on.

This means that when you buy those cleaning materials, you need to make sure you bill the client for them. If you’re not, you’re missing out on that revenue, and picking up the cost yourself.

Here’s the problem, though: each contract is different. One client may be happy to pay the cost of cleaning materials, and another might want that to be included in the fixed cost. One client might include quarterly carpet cleans in the fixed price, and another doesn’t, because they want the option to only do them every 6 months.

We had to make sure we were capturing the revenue we were entitled to. So we dug out the paper copy of each contract, and painstakingly made a schedule for each one of what was in scope, and what was out of scope. There were a bunch of things -- hand towels, mops, feminine hygiene products, landscaping, carpet cleaning, recycling, and so on -- that we documented for each of our contracts, and confirmed with our contract managers.

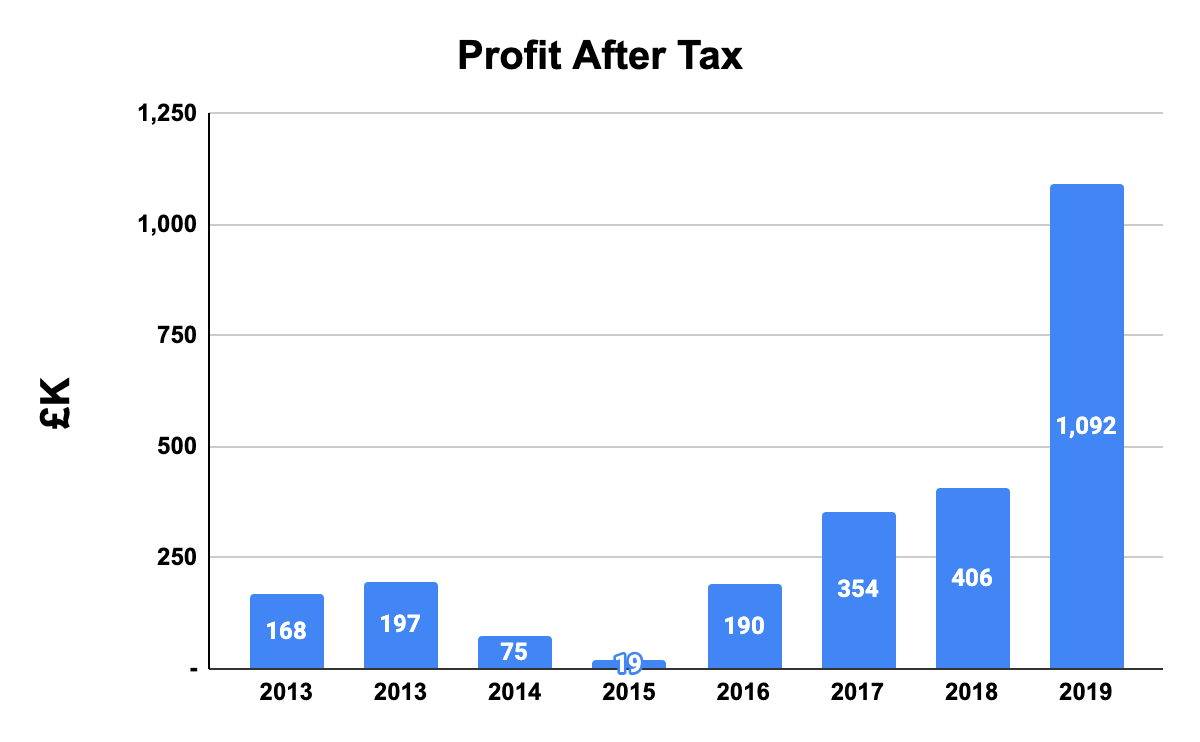

That was 2016, where we had accurate financials but not much of a budget. This is the P&L from that year:

10x the profit after tax despite revenue only increasing by c. 30%. Not bad. But we knew we could do better.

Step 3: Create reasonable, bottom-up budgets

By this point I’d been at the company just over 6 months. 2016 was a good year -- now we had to budget for 2017.

Thankfully, all the hard work we’d done up to this point made budgeting pretty straightforward. For each contract, we created a budget model, including the fixed fee charged to the client, and all of the labour and subcontractors we were obliged to provide under that contract. We checked this against the last few months of actual results to make sure it seemed reasonable.

Then, most importantly, we sat down with the individual contract managers to go through their budget line-by-line to make sure they a) agreed with it, and b) understood it.

All the contract managers had an opportunity to ask questions, clarify which costs they were responsible for, and understand how we’d arrived at the budget.

Then we sent them on their merry way (with the understanding that they now had a budget target to hit, and would be incentivised to hit it).

Over the next couple of years I ran monthly budget review meetings with every contract owner to discuss performance against budget, check any variances, and correct our numbers where we had to. These review meetings led to greater accuracy, less leakage, and greater commercial awareness all round.

From that point on, all our contracts were well managed and profitable. We were off to the races! All that was left was...

Step 4: Put together reasonable, well-costed bids to win more contracts

I take very little credit for this part. While I did a lot of the hard work in steps 1-3 to make sure the business was well run, winning new business was all thanks to the senior leaders in the organisation. They were great sales people with excellent relationships in the industry, and they drove the vast majority of the new business between 2016 and 2019

But I will take a little credit, for two reasons:

I helped to either create, or kick the tyres of, the cost models we used to price bids; and

All the work we’d done to make sure the business was well run gave other senior leaders more time to focus on winning new business, rather than running around putting out fires and trying to manage our existing business.

We were also able to be a little more strategic in which contracts we decided to bid for. We knew which of our existing contracts were the most profitable, so we could go after more like those. We knew we could keep the lights on with our current contracts, so we could be more discerning in what we decided to bid for, rather than chasing any opportunity we found. And so on.

The results

I joined the company in early 2016, and my boss and I did most of the hard work in 2016 to fix things, then we just kept a tight-run ship for the next couple of years. So while I only take a bit of credit for this revenue trajectory:

I will take quite a lot of credit for managing and maintaining this gross margin trajectory:

So we’ll split the credit for making this much money after tax:

And the owners can feel good about being able to take a good amount of profit out of the business for themselves even while growing the business:

So how much value did we create through the work we did? As I mentioned before, this isn’t a speculative investment on a growth stock. We’re not hoping that /r/wallstreetbets pumps up the value of the business so we can sell it tomorrow for a 100% gain. And it’s also not a hyper growth startup with a ton of stock options and early employees hoping for a big exit.

Instead, let’s say that this business is valued at 3 times after-tax earnings. At the end of 2015 that means the business was worth around £60k. At the end of 2019, it was worth £3.3M. That’s a gain of £3.24M in four years. Not bad.

Not only that, but in that time the business has paid out a total of £934K in dividends. So in four years we created over £4M of wealth, which all accrued to the company’s two owners.

Not bad for a little company from the north of England.

Those are the kind of opportunities you can find in the world of small business. You won’t get rich overnight, but if you’re willing to put in work over time, you can still make life-changing money. It just takes work.

And as an after-thought, the founder, Mark Cooper, sold this company in 2021 for an undisclosed amount — my guess is mid-seven figures, probably £5-8M — and sailed off into the sunset as he richly deserves to do.

Enjoyed this read Andrew, I like the beauty in the simplicity and the type of business you’re talking about - far more relatable. Would be interested to see/learn more about the automated dashboards you spoke about in point 1. Cheers.

Fantastic story, Andrew. I really enjoy your approach of simplifying complex ideas with the use of real life examples. I look forward to following this Substack!