Hello to the 1,513 people reading this, and a warm welcome to the 123 new subscribers since last week.

As a reminder, I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO here in the UK. Net Income is a weekly breakdown of the interesting companies I find. Or, in this case, a deep — some might say intrusive — look at the business and finances of a former professional athlete.

One request: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

I recently went to the movies to watch Air. It’s the story of how Sonny Vaccaro, played by Matt Damon, was a marketing executive at Nike in the company’s early underdog days. Sonny, through some combination of charm, persistence, and salesmanship, managed to land Michael Jordan as one of Nike’s marquee athletes.

In exchange, Jordan asked for a then-unprecedented term in his sponsorship agreement: a cut of all gross sales from any Jordan shoe that Nike sold.

Vaccaro and Nike agreed, and the rest is history. This deal transformed public perception of Nike, revolutionised sports marketing forever, and made Michael Jordan richer than Croesus.

In fact, did you know that Jordan made more money from that deal with Nike to put his name on a shoe than he ever did from playing basketball?

Of course you knew that. Everyone knows that.

It’s the most famous factoid in all of sports, up there with “Apparently Tiger Woods cheated on his wife.” Yeah, no kidding.

But we still love talking about it, don’t we?

This intersection of sports and business is fascinating, not just to me, but to everyone. Movies like Air, Moneyball, Jerry Maguire, and shows like Ballers, capture our imagination.

Who can resist the combo of famous athletes and big money deals? It’s a sexy topic so popular, it has its own Pompliano sibling. There’s a reason they turned the MJ/Nike story into a movie.

And there are some phenomenal examples of athlete-turned-entrepreneur stories.

My favourite of the genre is Junior Bridgeman. Having played 13 years in the NBA, and never making more than $350k a year, Bridgeman parlayed this modest career into a net worth of around $600m.

Bridgeman built his wealth by investing in fast-food franchises, even while he was still playing. He went as far as working in his locations during the off-season to get to grips with the business — and he just kept re-investing the profits in more and more franchises.

At its height, Bridgeman Foods, Inc, owned around 160 Wendy’s and 120 Chilli’s locations, with revenues of over $500m a year. In 2016, Bridgeman sold all his franchises, and with the proceeds bought a Coca-Cola bottling and distribution business.

Bridgeman’s franchise playbook has at least one dedicated disciple: Shaquille O’Neal.

Shaq followed Bridgeman’s example to a tee. At one point the former Lakers star was the largest Five Guys franchisor in the US, with around 10% of all locations (which he later sold). Shaq now owns, among other things, 17 Annie’s Pretzels, 9 Papa John’s, 150 car washes, and 40 gyms.

In fact I wouldn’t be surprised if Shaq launched a social media campaign telling people all about the wonderful opportunity of buying boring, cashflowing businesses, and then launched an online course.

But in the pantheon of athlete-entrepreneurs, neither Shaq nor Bridgeman can hold a candle to the true GOAT, his airness, Michael Jordan.

Jordan’s net worth is estimated at $2bn, even before he’s sold the Charlotte Hornets for a huge profit. Jordan continues to bring in around $100m a year from his Nike deal alone. As long as he doesn’t gamble it all away, he’s set for that /r/fatFIRE life.

Such is the glitz and the glamour of American sports.

But who’s doing the same over in the UK? Who’s our best athlete turned entrepreneur?

Who’s the British Michael Jordan?

And is it…

Gary Neville?

Spoilers: it’s not, but he’s doing a pretty good job anyway.

That most trusted and venerated British institution, the BBC, clearly think Gary Neville is a good example of an athlete-entrepreneur, because he’s going to appear as a guest star on the next season of Dragons Den.

British newspaper The Guardian estimates his net worth at £20m. Not bad at all. But is that right? What does he own? In what pies do we find Gary Neville’s fingers?

Let’s dive in.

Who is Gary Neville?

(Firstly, some ground rules: I know about a huge chunk of you are from the US, but for this piece, we’re using British words, British spellings, and British turns of phrase.)

Gary Neville was a professional footballer.

Not soccer player. Footballer.

Neville’s career began in the early 90s, as many careers did back then, with a boyish grin and a wonderful centre parting haircut.

Sport runs deep in Gary’s family:

Father Neville Neville (yes, really) was a cricketer.

Mother Julie was a netball player, and is now GM and Club Secretary for Bury FC, in England’s lower leagues.

Sister Tracey was an England international in netball, winning medals as both a player and a coach.

Brother Phil was a professional footballer, also coming through the ranks at Manchester United, before playing for England and Everton.

Gary continued that family sporting pedigree with an illustrious playing career.

A true one-club man, Neville played for Manchester United from his professional debut in 1992 until his retirement in 2011. He came into United’s senior team as part of the fabled Class of ‘92, along with , Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, Nicky Butt, his brother Phil and, most famously, David Beckham (another athlete-entrepreneur for another day).

Over 20 years, Neville racked up an impressive list of accomplishments:

400 senior appearances for Manchester United

85 England caps

8 Premier League titles

3 FA Cups

2 Champions League titles

1 FIFA World Club Cup

(but sadly, no partridge in a pear tree)

Solely from a sporting point of view, that’s a great career. But after hanging up his boots, Neville turned his hand to a number of other ventures, including TV, media, property, and education.

Thanks to the wonderful source that is Companies House, this is all public information too. So with some diligence and research, we can find out what Neville owns, and figure out how rich he is.

Mapping the Neville empire

The first step in our research process is to head to Companies House, and search for Neville’s name to see what companies he’s associated with.

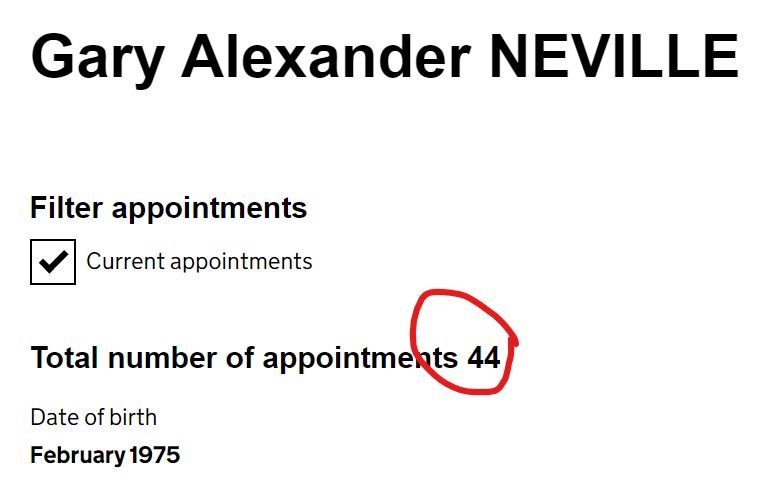

Here we are:

Oh, OK, 63 companies. That’s a lot. A bunch of them are probably dormant or dissolved, so let’s just filter for active companies, which should make the job easier.

God dammit Gary.

OK, let’s take a different tack.

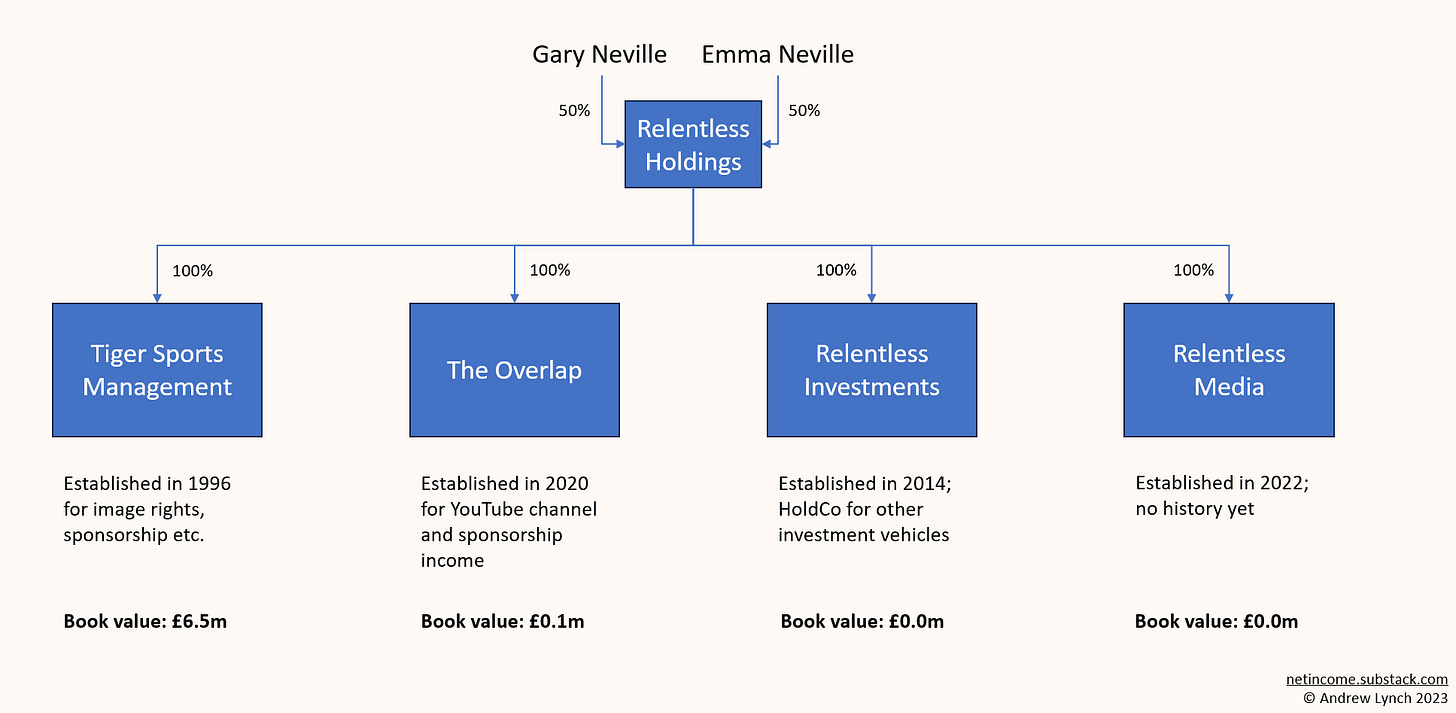

After a little scouting around I managed to identify Neville’s holding company: Relentless Holdings Limited.

Gary and his wife Emma each own 50% of Relentless Holdings, and in turn Relentless Holdings has four wholly-owned subsidiaries:

Relentless Investments

Relentless Media

The Overlap

Tiger Sports Management

Brief sidebar here to note that Gary Neville shares his love of the word ‘relentless’ with a certain Jeff Bezos.

Neville has included that word in a number of his company names, and his HoldCo. It’s an interesting glimpse into the man’s psychology — and it’s not surprising when you consider how Neville’s playing style is described on Wikipedia:

“Gary Neville was an aggressive, tenacious, and hard-tackling player, known for his work-rate, professionalism, determination, and consistency as a defender… [a]lthough he was not the quickest, tallest, strongest, most talented or most technically gifted player.”

Neville is a guy who made the absolute most of his talent through hard work and determination. Put another way, he was relentless. That idea of never giving up, of persevering, of getting everything you can out of a situation is clearly close to his heart, so he wants it represented in this small way through his company names.

Similarly, Amazon.com was almost called Relentless.com in the company’s early days. Bezos thought the word ‘relentless’ aptly described how he wanted his company to act, so he bought and registered the domain. To this day, relentless.com still redirects to Amazon.

Maybe Gary Neville has more in common with entrepreneurs than we originally thought.

Anyway, back to the Neville empire. If we dig in a bit more into each subsidiary, we end up with something like this:

To clarify: book value is the total assets of the company, minus all the liabilities. It’s what would theoretically be left over if you turned everything the company owns into cash, then paid off everything the company owes. It’s an imperfect measure — but most of these companies aren’t big enough to report a P&L, so the balance sheet is all we have to work with for now.

As a result, these four companies don’t look like much.

Tiger Sports Management, which has accumulated a bunch of profit over the years from Neville’s image rights, royalties, etc., is all of the value of this group. The Overlap, a recent creation for Neville’s YouTube channel of the same name, has a small amount of accumulated profit, and the other two companies have zero book value.

Let’s go further. Firstly, Relentless Holdings, the TopCo, has a book value of £1.5m itself.

Secondly, we can dive into the *counts* 25 subsidiaries of Relentless Investments.

I won’t bore you with all the details, but I went through every company that’s in the Relentless Holdings family, including subsidiaries of subsidiaries of subsidiaries.

After discarding any company that was dormant, dissolved, or had a book value of £100 or less, I came up with this list:

Purely looking at book value, the Relentless Group looks to be worth about £5.4m.

But wait, the devil is in the detail

Three things to note here.

Firstly, a bunch of these businesses have negative book value.

That’s usually because they’re borrowing money from other companies in the group, in what’s known as an inter-company loan or a related party transaction.

Those inter-company loans will drop the book value of the company borrowing the money, but should increase the book value of the company lending the money by the same amount — so it should all net out to zero.

Secondly, as I mentioned, only looking at book value is an imperfect measure, because it hides the underlying profitability of each business.

Let’s take the bottom business, The Man Behind The Curtain (Leeds) Ltd as an example. It’s a high-end restaurant that’s 50% owned by Gary and Emma Neville, and 50% owned by head chef Michael O’Hare.

All we have to go on is their balance sheet, which as at 31st Dec 2021 shows net assets of minus £81k.

But that’s understandable — it’s a restaurant, coming off the back of two Covid-impacted years. As at 31st Dec 2019, the company had net assets of £125k. Does that mean the business lost £206k in 2020-21? Well, maybe. Or maybe it made £500k in profit, and distributed out £706k to its owners. We can’t really tell. We just don’t have enough information.

Thirdly and finally, at least four of these companies are property investment vehicles — which means the book value of their assets might not reflect reality.

Are Neville’s assets understated?

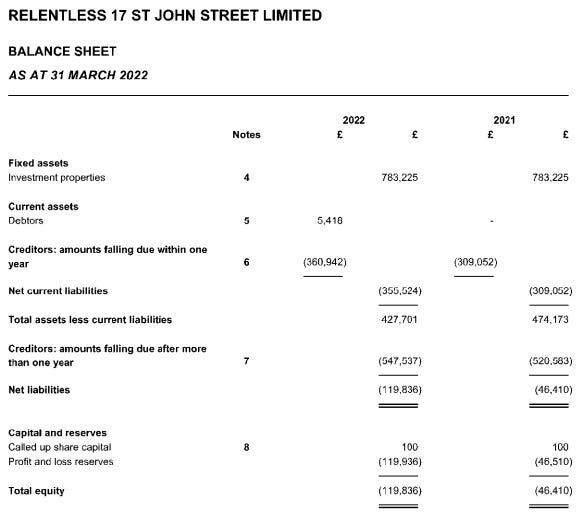

As an example, let’s look at Relentless 17 St John Street. This is a company specifically created just to hold an investment property. This investment property, to be precise:

It’s a lovely, period commercial property in a fantastic location — right in the heart of Manchester, a city which has seen a huge boom in recent years. Think Austin, Texas, but with more rain and Britpop bands.

Relentless 17 St John Street is a fairly simple balance sheet then: the assets are the investment property, valued at £783k, and the liabilities are the money the company has borrowed to buy those assets.

So far, so good.

But wait — they’re valuing the property at £783k this year, just like they did last year, and the year before?

How can a property valued at £783k in March 2020 still be worth exactly the same in March 2022? Seems sus imo.

In fact, with a bit of data wizardry (downloading a CSV), we can take figures from Land Registry for average property prices in Manchester, index them back to March 2020 when Neville first acquired the property, and see how prices in the city have changed since.

Looks like average property prices are up 20.7% in those two years.

Again, this is an imperfect comparison because these figures are for residential property, rather than commercial, but nonetheless, they’re an indication of the direction in which prices have gone.

Which means we could do some restatement of Neville’s numbers:

All of a sudden we’ve increased the net worth of Relentless 17 St John Street Ltd — and therefore Gary Neville himself — by £162k.

Now, let’s recap:

no P&L

asset values likely don’t reflect market reality

Multiply those two issues by 18 subsidiary companies, and we come to the conclusion: I don’t have a clue how much Gary Neville is worth.

In fact, it gets even worse when we try and account for Neville’s minority investments, which I’ve detailed here:

One more time for fun: this is an imperfect analysis, but using just book value, Neville’s share of these minority investments means he’s £4.5m in the hole.

So let’s smash this analysis together and see where we end up:

Damn. Is Gary Neville even a millionaire?

Did he play elite level football for 20 years only to piss most of his money away on hotels and unprofitable lower league football clubs? Is he less of a Shaquille O’Neal, and more of a Dennis Rodman?

And really, should he be on Dragons Den, dishing out investment, when it looks like he’s one unexpected electricity bill from declaring bankruptcy?

Not so fast

Neville’s probably not on the verge of bankruptcy, let’s be honest. I don’t know if he’s worth £20m — what we’ve uncovered so far suggests not — but let’s look at why the value of all his companies might not look that impressive on paper.

There are four possible explanations. These are speculation, and I have no idea which one is correct, but all are possible.

Explanation #1: high distributions

It’s entirely possible that the reason Neville’s companies don’t look that flush with cash is because they generate a high amount of profit every year, and Gary Neville and his wife take a bunch out in distributions each year.

They’ll pay their UK tax on it, then invest it personally in their own names in a combo of tax-advantaged accounts, private investment trusts, and other assets that we can’t see through Companies House or other public domain information.

Explanation #2: offshore investments

Neville and the rest of the Class of ‘92 have a close business relationship with Singaporean investor Peter Lim, who co-owns Salford City FC with the group. It was Lim who bought the majority share in the imaginatively named Hotel Football and Café Football when the Class of ‘92 sold their shares. Neville and Giggs are still directors of GG Hospitality Management Ltd, the company behind those two venues, but that business is now owned by GG Collections Private Ltd, in the British Virgin Islands, which in turn is owned by Thomson Medical Group Ltd, in Singapore.

So as an example, either Neville cashed out his shares, paid tax, and then invested the proceeds personally rather than through his companies, or he holds shares in the offshore companies, facilitated by Lim.

Explanation #3: reducing tax burden

Going back to 17 St John Street as an example: the reason the asset value might be understated is because restating the value of property upwards leads to a taxable gain, meaning tax to pay. And who wants to do that?

I sure don’t, and Neville probably doesn’t either. So he might be keeping the value of his assets artificially low to avoid tax — or at the very least, he’s not enthusiastically revaluing his property every year.

To be fair to him, that’s not really tax avoidance — it’s actually fairly common practice when it’s hard to get a true market value on what your assets are worth — but it does have the beneficial side effect of reducing tax, which no one ever in the history of mankind has ever thought of as a problem.

Explanation #4: the numbers are broadly right, and Neville’s just not a very good entrepreneur

You can call yourself and everything you own Relentless, but if you’re spending £1 to make £0.90, and you keep doing that for a few years, you won’t have much left at the end of it.

So which is it?

If I had to guess, I’d probably say a combo of #1, high distributions, and #3, some mild tax optimisation.

To be clear, I don’t think Neville’s a terrible entrepreneur. And he doesn’t seem like the type to engage in huge tax fraud either. He’s probably just taking a bunch of money out of his companies each year, paying his taxes, investing some money personally, and then funding his lifestyle and his love of loss-making Salford City FC.

So is Gary Neville the British Michael Jordan?

Sad to report: no, he’s not.

Gary Neville is to Michael Jordan what I am to the incredible Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine. He’s more British, with less natural talent and athleticism, and a lot less money — but he’s trying hard, and his heart’s in the right place.

Carveouts

I finished Will Thorndike’s book The Outsiders, and wanted to dive deeper into the story of John Malone and TCI, so I started reading Marc Robichaux’s book Cable Cowboy. Fun fact: John Malone was the guy who invented the concept of EBITDA. Recommend checking it out, it’s a great read.

As always, thanks for reading — see you next week.

Andrew

Great read! Thank you.

Suggestion for next story- someone not well known but with incredible empire through various boring/cashflow/franchise business..