From £2m to £200m: how to scale a people business

A story of rapid growth in the consulting industry

Hello to the 975 people reading this, and a warm welcome to the 702 new subscribers since last week. From the poop business last week, to the people business this week — here’s your satisfying serving of business breakdowns.

As a reminder, I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO here in the UK. Net Income is a weekly breakdown of the interesting companies I come across. I’m like Sam Parr’s poorer, not-as-good-looking British cousin.

One request: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

I think Paul Graham is wrong.

I know, I know, that’s heresy.

The Y Combinator founder is venerated, idolised, worshipped by the Silicon Valley tech crowd. People hang on his every word, and his essays are stuff of legend.

But Paul also says stupid things.

In this instance, I’m thinking of his essay Do Things That Don’t Scale, in which Paul blithely states:

Consulting is the canonical example of work that doesn't scale.

Well, tell that to this consulting firm based in London:

This is Baringa Partners LLP.

Since Baringa’s inception in early 2002, they’ve grown revenue at an average rate of 30% per year — for twenty straight years. According to the founder, Mohamed Mansour, in those twenty years they’ve had just one unprofitable month.

What should I do, Paul Graham? Go and tell them that consulting doesn’t scale?

Their growth story demonstrates some great themes: spin-offs, incubating new business lines, and the idea of selling your sawdust.

Let’s get into it.

Quick note: there’s a lot of data and images in today’s post. If you want those for yourself, including the full P&L data going back to Baringa’s inception in 2002, I’ve made them available here:

You’ll get the files emailed to you as soon as you’ve finished checking out.

Wait, what is consulting?

It’s easy to make fun of management consulting. If you google “consulting jokes,” you’ll find a ton. A consultant is someone who steals your watch and tells you the time. That sort of thing. Management consulting is seen as such a rich vein of humour that HBO went as far as making a TV show about the whole thing:

Spoilers: it was not very good.

Fundamentally, management consultants are people you hire to help your business solve a problem. That could be adapting to changing regulation, implementing a new IT system, or expanding internationally. You, the business leader, can’t solve those problems alone, so you hire consultants to help you.

Why not just hire full-time people instead? Three main reasons:

You genuinely need expert, outside resource: people who have done what you need to do, for other companies just like yours, in your industry. People who are so good, they don’t want a full-time role with you.

You need high-level temp resource. Not those minimum-wage temps that can only file and fetch coffee. Actual, hard-working, Excel wizard, know-some-stuff, Harvard MBA-kinda temps. You need them for 6 months for a fixed term project, then you can cut them loose when you’re done.

You need career insurance. Your company needs to make a big strategic change — but if you do it, and it fails, you’re fired. So you hire consultants, they write a nice report that details their recommendations (which coincidentally line up perfectly with what you already think), and you give that report to your boss. Then, if you execute that strategy and it fails: hey, it’s not your fault, we just followed the consultant’s recommendation.1

(I know, so cynical.)

At its heart, consulting is a people business. Really it’s the same labour arbitrage that temp agencies do every day. Hire someone on one rate, bill them out at a higher rate, pocket the difference. Your people are the product — and it’s on you to keep them busy and earning revenue.

How do you do that? Again, it’s a people business: the selling process is up close and personal. You need to find and meet potential clients, and get them to like you, and trust that you and your team can solve their problem.

The good news is that if you get it right, it’s incredibly profitable. Here’s Baringa’s P&L for 2021 and 2022:

70% gross margins, and £185m in profit on just £268m of revenue.

In 2022, Baringa had an average of 1,089 employees. For now, I’m excluding that suspiciously vague other operating income of £74.4m — more on that later — but here’s how the simple labour arbitrage breaks down on a per-employee basis:

Not bad at all. Even taking into account employees that don’t earn revenue (like Finance, HR, and IT) Baringa makes £246k of revenue per employee, and spends only £144k, including salary, bonus, travel, and all other overheads. The highly profitable, cash-generating labour arbitrate consulting model is alive and well.

Here’s a simplified view of their five-year P&L. I’ve split out the other operating income to show the vanilla consulting model:

Like clockwork, this consulting business generates around 40% operating margins, every year. Profit per employee is steady, between £85k and £109k per year.

This drives home just how much of a people business this is. Want to grow? Hire more people, and bill them out. It’s that simple.

Check out the revenue per partner too. It’s flat year over year, even as the company more than doubled revenue. Whatever the size, they’re at almost exactly £2m per partner, per year.

That reveals Baringa’s growth strategy:

Hire a partner with their own expertise, reputation and great industry relationships.

Give them a £2m revenue target and a team of 6-7 consultants to deliver the work.

????

Profit

Note: the ???? in the growth strategy reflects the fact that I’ve never worked in management consulting, and I have no idea what actually goes on in the delivery phase.

If you work in consulting, yes, I think it’s a real job, and yes, your parents are proud of you. I know you could have been a doctor, but hey, those PowerPoint slides won’t design themselves, will they?

Looking at the P&L in more detail, two things stand out. Firstly, the margins are extraordinarily high. Secondly, why does Baringa pay almost no tax?

Because this company isn’t a normal company. It’s a partnership.

The partnership model

Baringa Partners is an LLP, a Limited Liability Partnership. LLPs are different to limited companies (or LLCs). They don’t have shareholders or directors. They have partners.

LLPs are common in professional services firms like mangement consultants, and lawyers, precisely because these are people businesses.

An LLP structure means that if you find a great person who can bring in tons of revenue to your company, you just make them a partner. You don’t have to issue equity, or give them share options, or mess around with your cap table. A simple partner vote, and they’re in.

And if someone isn’t pulling their weight, a simple partner vote, and they’re out.

As an aside, this is why “making partner” in a law firm or consulting firm is such a big deal. It’s not just a promotion, a pay rise, or a fancy title. It’s a piece of the action.

How big a piece? Well, in 2022 Baringa had 114 partners, sharing profit of £185m. That’s an average of £1.6m per partner. Even excluding the one-off profit bump of £74m, it’s £974k per partner.

There are two other quirks of the LLP structure to be aware of:

That partner remuneration of £1.6m each does not show up on the P&L. The P&L excludes all partner comp, because whatever is left over after paying all the other costs — employees, expenses, office leases — gets split between the partners, according to their partnership agreement. That’s why the margins look so fat: the partners are earning revenue as well, but their costs aren’t included.

Baringa Partners LLP, as an entity, doesn’t pay much tax, because a partnership structure is designed to pass all the profits to the partners. Rather than a limited company which pays tax on its profits, then distributes the remainder to shareholders, a partnership passes all the profit to the individual partners, who then personally pay the tax on their share of the profits.

Here’s a visual representation:

Let’s look at the 2022 figures. On average, each partner brought in £2.3m of revenue with a team of around 7 consultants and 1.6 admin staff.

Breaking that down, here’s how the numbers look:

The £2.3m revenue covers £1m of consulting costs, and £231k of overheads, leaving around £1.1m profit per partner, which they take home as their personal income. That’s an average — the (confidential) partnership agreement will detail the exact split between the partners — but it’s good enough for our purposes.

You see? This isn’t one business: it’s a federation. A franchise model. Each partner is running their own small business, under the Baringa brand.

That’s how partnerships work. You live and die by your ability to bring in revenue. To make it rain.

This federated model could lead to conflicts though — every one of your 114 partners has a stake in the brand name of the company. That could be hard to manage — but among those partners, there is a “first among equals,” known as the Managing Partner.

This brings us on to the origin story of Baringa, and the wonderful world of spinoff companies.

Don’t start a consulting business from scratch

Baringa was actually started back in 2000, as the European arm of a US consulting company called The Structure Group, or TSG.

TSG was based in Houston, Texas, and its main area of expertise was the oil and gas industry. Seeing many of its clients expand into Europe, TSG wanted to do the same, so tapped up three smart guys to go establish TSG Europe over in London.

Those three guys were Andrew Chittenden, Jim Hayward, and the original Baringa Managing Partner, Mohamed Mansour.2

After Enron collapsed in late 2001, many of TSG’s energy clients retreated from Europe back to the US, leaving Andrew, Jim and Mohamed with a choice: follow the clients back across the Atlantic, or forge onwards and build a business in Europe.

Like Shackleton, they chose to forge ahead.

But — here’s the crucial point — at this point they’d already been consulting in London for 3 years under a different brand.

They’d used the TSG name to build their relationships and reputation, and then when the opportunity presented itself, they span off into a separate business, with TSG keeping a stake.

Sidebar: this is similar to how TSG itself started. The founding partners were all at Accenture (then Andersen Consulting), and all their clients were in the energy industry. Those guys built up their network and reputation at Accenture, then when they felt ready, went out on their own, targeting those same clients. They did so successfully until 2015, when they were acquired by — you guessed it — Accenture.

So in 2002, Baringa was essentially a spinoff of a spinoff. Andrew, Jim and Mohamed set up at first to specifically focus on the energy industry, as that’s where their specific expertise, reputation and network was.

To highlight just how crucial the right people are to making it in the consulting business, Mansour candidly admits in an interview, referring to his other founding partners:

“No two of us could have done it without the third.”

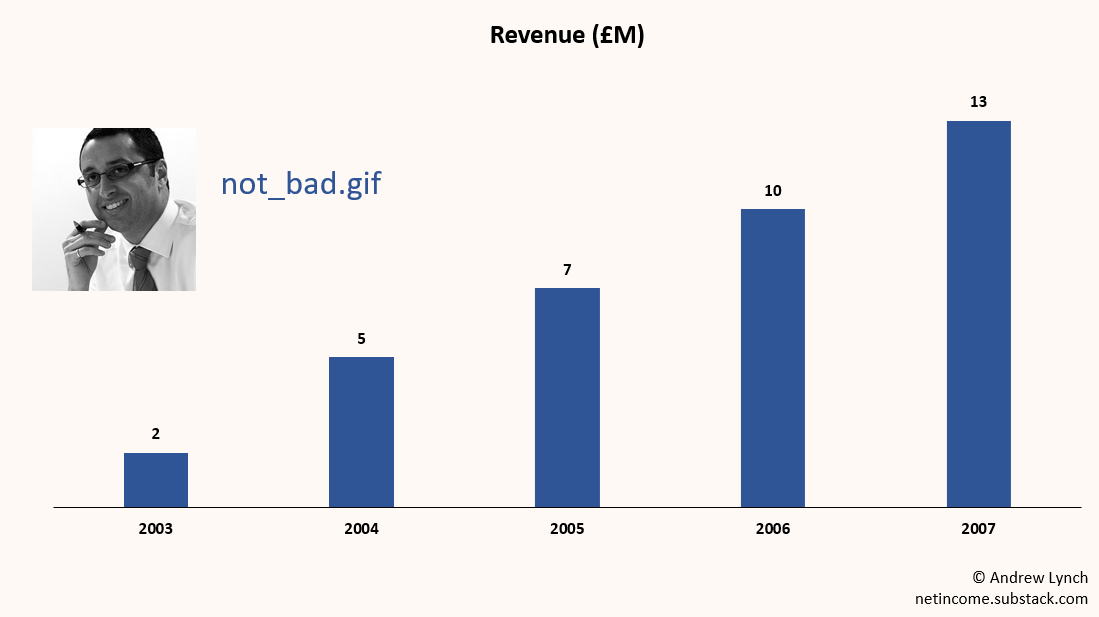

This alchemical mix of talent led to rapid early growth. Here’s how revenue grew under the leadership of Mansour (pictured below) in the early days:

By 2007, the company had 11 partners, and another 38 staff, and was growing nicely.

But Baringa was still only serving clients in the energy industry. They wanted to diversify and add a new, lucrative practice area: financial services. So what did they do?

Well, this being a people business, driven by expertise, relationships and reputation, they went out and hired a partner to lead that new practice area.

Enter Adrian Bettridge.

Adrian was a veteran of — yes — Accenture, where he’d made partner at a young age. But Adrian had an entrepreneurial bent, and wasn’t happy with the status quo at such a large company. In Adrian’s words3, after making partner at Accenture:

“I felt like I’d made it to the top of the tree and I was in the wrong jungle.”

Climbing down that tree and scanning for an alternative arboreal climbing challenge, Bettridge met Mansour. They clicked immediately. Here’s an artist’s rendition of that first meeting:

Adrian joined Baringa in 2007, bringing with him a career’s worth of expertise, relationships and reputation in the financial services industry.

Starting to see the pattern here?

With Mansour heading up their energy practice, and Bettridge (pictured below) leading FS, Baringa took off. Even the Great Financial Crisis in 2008-09 did nothing to slow their growth.

Mansour retired in 2015, at which point Bettridge took over as Managing Partner.

Baringa have since added practices in Telecoms and Media (2014), Consumer products and retail (2016), Pharma and Life Sciences (2019) and Government Advisory (2019). They’ve also opened offices in the US, the UAE, Australia, Singapore, and mainland Europe.

Each time, they’ve followed the same playbook: find who has built their expertise, relationships and reputation at another firm, and wants to do something entrepreneurial — and poach them.

That new partner comes in, using their existing reputation to generate more revenue, and hires a team to deliver that work.

The result: every new practice lead and partner essentially incubates then operates their own business, using the Baringa brand, resources and infrastructure as a platform.

As long as Baringa can stick to around £2m revenue per partner, and each partner can use 6-7 consultants to deliver that work, they can keep scaling.

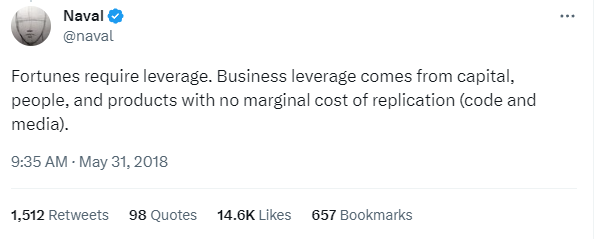

That’s what Paul Graham forgot to say — and what everyone’s favourite angel investor turned philospher Naval Ravikant pointed out.

Leverage can come from people as much as it can from capital, code and media.

What Paul Graham should have said is “Consulting is the canonical example of work that doesn't scale unless you can hire more people.”

It’s the classic tradeoff. Paul Graham’s world, software, is hard to start and turn profitable, but does have the potential to scale massively. In that industry, WhatsApp is the canonical example: at the time they were acquired by Meta for $19bn, they had just 55 employees. That’s leverage from code.

On the flipside, Baringa has leverage from people. In their history they’ve never had a loss-making year, and the company needs almost no extra capital to expand.

As a result, Baringa throws off gobs of cash every year. Almost all the profit it makes turns into cash that can be distributed to its partners:

Entrepreneur and investor Andrew Wilkinson, the founder of Tiny, summed up this dilemma between scalabilty and cash flow nicely:

“Every consulting company owner I know wants to own a SaaS software company. Every SaaS software company owner I know wants to own a consulting business. The grass is always greener.”

But Andrew:

Can you have the cashflow of a services company with the scalability of software?

Sometimes, yes.

Let’s look at the last piece of the puzzle.

The curious case of £74m other operating income

For the final lesson from Baringa’s growth story, let’s go back to their 2022 P&L.

One of these numbers does not belong.

Other operating income is so vague, and the number is so big. What on earth could they have done to generate an extra £74.4m in one year?

Note 5 is where we’ll find the juicy details.

Oh dang! Internally developed software. I thought this was a consulting company?

For an upfront payment of $35M, plus future payments of around $69M, Baringa sold a piece of software they’d built themselves.

What was this software? After a bit of googling, we find out:

Here’s the press release for more info.

Baringa spent years consulting to the energy industry. Over that time they built an advanced, complex model to help clients examine the impact of different climate change scenarios:

Baringa developed its market-leading climate scenario modelling capabilities on 20 years of experience. Baringa’s solutions support net zero commitments, TCFD reporting, regulatory reporting, investment and capital allocation strategies, as well as developing climate risk management capabilities. As the leading solution in the financial services sector, Baringa’s Climate Change Scenario Model is informing clients with assets totalling more than $15 trillion.

Baringa built their climate change model to help them better serve clients. Over time, that model became a significant asset in itself — so much so they could sell it, to the tune of $100m.

A consulting firm, and a software firm. Beautiful.

The founders of software company Basecamp, Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson, describe this in their book ReWork as selling your sawdust.

To sell your sawdust is to examine the by-products of your work, and see if they have commercial value on their own.

For lumber industry, that’s the sawdust they generate while cutting wood, which goes into synthetic logs. For Fried and Hansson, it’s the principles on building and operating software companies that they’ve codified, and packaging that into a book. For me, it could be the spreadsheets, PowerPoints and memes that have lovingly been crafted in service of this article.

And for Baringa, it’s a climate change model they built during years of consulting — that they sold for $100M.

Not just a consulting firm after all.

Key takeaways

Let’s wrap up, because I actually also have a day job I need to get back to.

Baringa is a phenomenal example of scaling in a difficult-to-scale business. Paul Graham’s not totally wrong. Consulting is difficult to scale unless you can keep finding and hiring great people.

Baringa are also an amazing example of just how lucrative and cash-generating the consulting business can be — especially if you’re building assets along the way.

The key takeaways from the Baringa growth story:

Pick your poison. Software is hard to start because it’s high fixed cost, and it can take you a long time to get cashflow positive. Consulting is cashflow positive almost from day one — but scaling is more difficult. Any business model will have challenges. Just pick one and get going.

To grow a people business, hire people who will bring revenue with them. People who have been there, done that, and have the network and reputation to prove it — and give them a more entrepreneurial opportunity.

Sell your sawdust. Look for the by-products you’re creating while doing the work. They might be more valuable than you think.

If you do those for 20 years, maybe one day I’ll write an article about you too.

Carveouts

I’ve been re-reading Steven Pressfield’s book Turning Pro. If you’re trying to do anything creative or entrepreneurial, I highly recommend it. It’s a wonderful and honest look at the differences between amateurs and professionals. For a taster, check out this article on Pressfield’s idea of “shadow careers.”

Ted Lasso season 3: we’re about halfway through so far. Much better than season 2, and possibly as good as season 1. Aside from Parks and Recreation I don’t remember a show ever being as feel-good as this.

So long until next week!

Andrew

This is similar in nature to the adage that “no one ever got fired for buying IBM.” No one ever got fired by following McKinsey’s advice.

I’m indebted here to the Climb In Consulting podcast, where Mohamed gave this interview discussing the Baringa origin story.

Fantastic read!

This is incredible. Thanks for sharing Andrew.