Getting price-gouged by private equity in the UK's happiest resort

Trees, bicycles, quiet pints by the lake, and taking out £1.9bn of debt to have it all

Hello to the 1,173 people reading this, and a warm welcome to the 198 new subscribers since last week. If you go down to the woods today, you’re sure of a big surprise: a giant private equity deal in the making.

As a reminder, I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO here in the UK. Net Income is a weekly breakdown of the interesting companies I come across. Imagine if one of the people off Dragons Den was actually young, likeable and with some charisma, but not as cool as Steven Bartlett.

One request: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

It’s hard to enjoy yourself when your eyeballs are being ripped out.

You know, that feeling when you’re being squeezed for every penny? There’s not much you can do to shake it.

You can try to relax. You tell yourself, “I’m on holiday, it’s not real money! You only live once, just enjoy yourself.”

But in your bones, you feel it. Every swipe of the card is another papercut on your soul. That’s just too expensive.

For my readers outside the UK, we sometimes refer to this as being “mugged off.” Taken for a ride. Swindled, blagged, robbed.

But if at the same time, your kids are safe, they’re being civil to each other, and the whole family is having the time of their lives on the water slide, is being mugged off a fair price to pay?

Today’s company would argue that yes, it is a price worth paying.

This is, of course, the story of Center Parcs.

Quick note: there’s a lot of data and images in today’s post. If you want those for yourself, I’ve made them available here:

You’ll get the files emailed to you as soon as you’ve finished checking out.

The UK’s happiest place

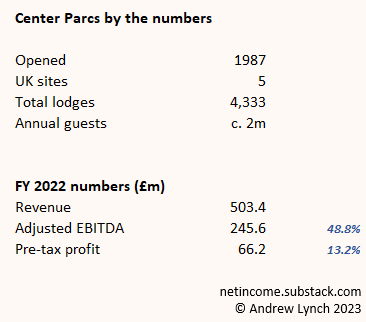

Again, for my readers outside of the British Isles, let’s make sure we’re all on the same page. First, some headline figures to level set:

Center Parcs UK operates six leisure and hospitality sites around the UK and Ireland. These sites are all ensconced deep within wooded forests, with a ton of amenities on site like bars, restaurants, swimming pools, archery courses, mountain biking, paintball, and more.

They all kinda look like this:

All the guests stay in individual lodges, like this:

And every Center Parcs site has a huge swimming pool, like this:

They are fantastic places to go on a family getaway.

Center Parcs came to the UK in 1987, having already established itself in mainland Europe, which is why it’s spelled in the somewhat Francophile Center Parcs, and not Centre Parks. (I thought this is why we did Brexit?)

The first UK site was built in Sherwood Forest (yes, that one, from the Robin Hood legends). Since then, Center Parcs have opened four more across the UK, and another in Ireland. They now have over 4,000 lodges, serving approximately 2m customers per year.

Each site is huge — acres and acres of woodland — and because guests only arrive and depart two days per week (Mondays and Friday), the sites are also blissfully quiet and car-free. That makes them safe and pleasant to get around, either on foot or by bike.

Imagine: getting the whole family on their bikes, leisurely cycling down to the restaurant to enjoy a pint and some dinner, then heading off to a bar for a couple more scoops1 while your kids head off to the table tennis area to occupy themselves. Later, you all saunter back to your lodge, the kids go to bed, and you and your spouse enjoy a quiet glass of wine on the patio and listen to the sound of trees rustling in the cool summer breeze.

I’ve only stayed at Center Parcs once, with a group of friends. As someone who loves the outdoors, cycling, adventure sports, and a pint or two, it was glorious. A truly idyllic weekend.

And yet…

At this point in our story, I’m reminded of one of my favourite books and movies, The Big Short.

Ryan Gosling’s character, Jared Vennett, is pitching to Vinny Daniel, played by Jeremy Strong. Jared wants Vinny to buy some of his credit default swaps. It’s a wonderful deal, says Jared. You’ll make a killing. Vinny, ever the sceptic, can't understand why Jared is pitching him this deal if it’s so good. Why is Vinny the lucky one?

“Swaps are a dark market. I set the price, whatever price I want. So when you come for the payday, I’m gonna rip your eyes out. I’m gonna make a fortune. The good news is you’re not gonna care because you’re gonna make so much f**king money.”

Well, the pricing team at Center Parcs know what they have. The market for high-quality forest lodges is a dark market.

They know how much you’d love to take your family there. They know you can’t resist that feeling of biking down a quiet road, surrounded on all sides by 50ft trees. Not a care in the world. At one with nature. The feeling that this is what life is all about.

So if you want that feeling, they’re gonna rip your eyes out. They’re gonna make a fortune. And hope you don’t care because you’re gonna have such a good f**king time.

As an example, watch the price of a family-sized lodge miraculously double from one week to the next, thanks to school holidays.

Why so aggressive on the pricing? Well, firstly because they can. Their lodges are a cornered resource2, in limited supply, so they get to set the prices.

And secondly, because Center Parcs UK is owned by a huge private equity firm, Brookfield Property Partners, and they want to get paid.

Center Parcs has changed hands a few times, actually. Back in 2001, Center Parcs UK was split from Center Parcs Europe, then sold to Deutsche Bank, who took it through an IPO in 2003.

In 2006, the Blackstone Group bought Center Parcs UK, and took it private. They spent a bunch of money to upgrade it, then in 2015, sold it on to its current owners, Brookfield, for around £2.4bn.3 (source)

Brookfield in turn spent a bunch of money upgrading the sites and the systems and infrastructure of the business. Now, having owned it for seven years, Brookfield is looking to sell again.

Depending on the timing of the sale, Brookfield are hoping to get as much as £5bn from the sale.

Will they get £5bn? Is Center Parcs worth £5bn? In fact, how much money does Center Parcs actually make? Let’s answer all of these questions and more.

Today, we’ll cover:

What the hell is private equity?

How much money does Center Parcs actually make?

Capital-intensive vs. capital-light businesses

How to value Center Parcs

Let’s get into it.

(Introduction completion fee: £4.99)

Wait, what actually is Private Equity?

Private equity, or PE, basically just means “buying and selling ownership interest in companies that aren’t listed on the stock market.”

Equity means the value of shares issued by a company. Amazon and your local corner shop are both companies, they both sell products to consumers, and they’re both ultimately owned by either one or multiple people.

The difference: if you want to buy 100 shares of Amazon (not investment advice, read the disclaimer) on the NASDAQ, any member of the public can log on to a computer and do so at a moment’s notice, assuming the market is open. Amazon is a public company, whose shares trade on the public market, which is the place where you can buy and sell public equities.

On the other hand, if you want to invest in your local corner shop, you can’t just do that online. You need to find the person or people who own it, get them around a table, and cut a deal. It’s a private company, which you buy or sell on the private market -- which basically just means ‘everything that isn’t the public market.’

So, simply put, private equity (PE) is buying and selling shares in private companies. Ideally, in an effort to make money.

Still with me?

How do PE firms actually do that? With a combination of money raised from investors (equity) and money borrowed from banks (debt).

The issue is that investors want their money back at some point, so most PE funds will have a life of around 7-10 years. The investors give the PE fund money in 2014, and the PE fund promises to give it back to them by 2024, hopefully with a good return on top.

That’s why these headlines are almost exactly seven years apart.

Brookfield must be coming to the end of its fund term, and needs to sell Center Parcs to be able to return capital to its investors. It’s no more complex than that. Such is the life of a PE fund4.

How much money does Center Parcs actually make?

In its last full financial year, 2021-22 year, Center Parcs did:

Revenue of £503.4m

EBITDA of £245.6m

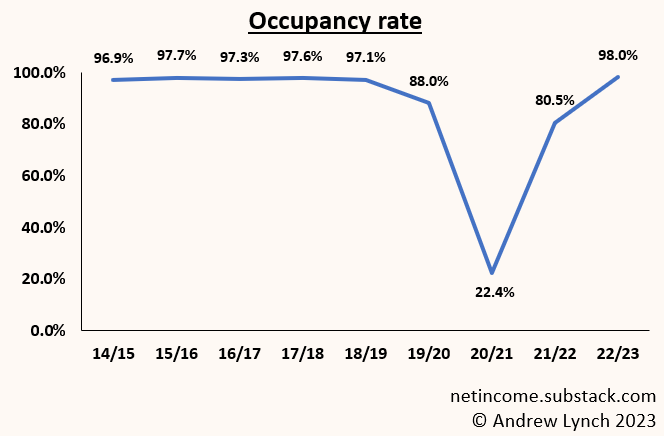

That’s despite occupancy only being around 80.5%, still well below their pre-Covid levels of 97-98%. Center Parcs also track a couple of hospitality specific metrics:

ADR is Average Daily Rate, e.g. the total accommodation revenue, divided by number of lodge nights sold.

RevPAL is Revenue Per Available Lodge Night. In most hotel businesses you’d call this RevPAR because most hotels sell rooms, not lodges, but Center Parcs is special like that.

Center Parcs has only released three quarters worth of results for the 22-23 financial year, but they look damn good. I’ve estimated the full-year results here, and compared to prior years. Their financial year runs from May to April, meaning the 18/19 year is the last full year with no Covid impact.

Looks like they’ll do over £600m in revenue this year, which is a big improvement on pre-Covid.

Lastly, let’s zoom out a few more years and look at how this company has performed over the period Brookfield has owned it.

Revenue is growing at a steady clip, and recovered incredibly quickly post-Covid.

EBITDA is looking damn fine too.

And finally, occupancy is back up to — and even above — pre-Covid levels, hence why 2023 revenue is around 20% better than the prior year.

The obvious thing to point out is that Covid was brutal for Center Parcs, and the impacts lingered for a long while. Now they’re clear and on the other side of it, they’re firing on all cylinders again.

Here’s a look at the P&L in a little more detail. I’m keeping it to 2018-2022 to show the last full year results with no Covid impact.

Those margins are fantastic. 71-75% gross margins, and 48% EBITDA margins. Wonderful.

Digging into the numbers:

About 60% of revenue is accommodation revenue (the cost to actually book the lodge)

40% of revenue is on-site spend

Put another way, if you’re the mug who spent £4,299 on a family lodge for the week, Center Parcs reasonably expect you to spend another £2,900 on site when you’re there. Beers, meals out, paintballing, bike hire: it all adds up, quickly.

The on-site spend is also high-margin because the prices in their restaurants and bars are expensive, particularly compared to the quality of the food. £18 for a burger. £6 for a pint of lager. £28 for a mediocre steak.

Of course their gross margins are high. Anyone can make 75% gross margins if they sell Wetherspoons food at Hawksmoor prices.

Translation for the North American readers: Anyone can make 75% gross margins if they sell Olive Garden food at Ruth’s Chris prices.

But still, you’re not there for the food, you’re there for the experience. You grit your teeth and get on with it.

So that leaves Center Parcs with nearly 50% EBITDA margins. Not bad, eh?

But obviously there’s more to the story.

EBITDA is Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation, and Amortisation.5

So it’s not a great measure of profit for Center Parcs, because they have a LOT of ITDA.

Here’s the rest of the P&L:

Excluding 2021, their average EBITDA margin is 47.5%.

But their average net margin is just 8.4%. Even in 2019, fully pre-Covid, the net margin was only 13.1%.

Using 2019 as an example, £232.6m of EBITDA only turns into £62.8m of net income. The rest disappears into the ITDA ether.

Two things are crucial here:

Center Parcs is an incredibly capital-intensive business, which means a lot of depreciation; and

Because Center Parcs is owned by PE, the company is also carrying a ton of debt.

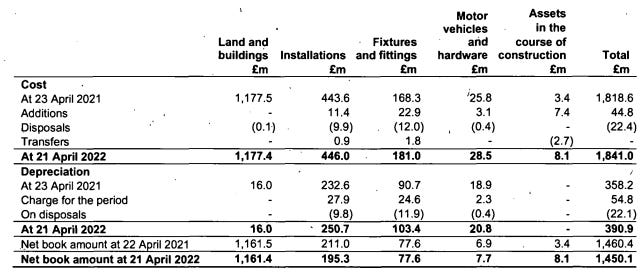

First, let’s look at that capital intensity.

Capital intensity

By capital-intensive, we just mean: how effectively does the business turn what it owns into revenue?

We can quantify that using the asset turnover ratio, which is:

Asset turnover ratio = Revenue / average assets

We’ve looked at a couple of businesses recently, Baringa and Petex, which are relatively capital-light. Here’s how they compare to Center Parcs:

Baringa is a very capital-light business: they’re mostly selling people. For every pound they have in assets, they generate £1.46 in revenue per year.

Petex, a SaaS company, is slightly more capital-intense: for every £1 of assets, they generate £0.96 per year of revenue.

Way, way down the pecking order is Center Parcs, who generate just £0.26 per year of revenue for every £1 of assets. They have £1.9bn of assets, and nearly £1.5bn of that is fixed assets:

That represents all the land, lodges, bars, restaurants, car parks, computer systems and more that it takes to run such a big business.

Not only that, but the land, lodges, swimming pools, bars etc. all constantly need repairing, replacing and upgrading. Over the last ten years, Center Parcs has spent £542.9m on capex. Even just since Brookfield took over, they’ve spent £468m.

In their investor updates, Center Parcs split that into investment capital and maintenance capital. The former is focused on improving the business; the latter is what Center Parcs needs to spend just to stay still.

According to this half-year update, that just-to-stand-still number is £16m in the first half of the year alone.

That’s a big number. They’re spending millions on water slides. Literally, this is next in the presentation:

Now, this capital intensity isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It takes a ton of capital to maintain and grow the business — but that also keeps competition out.

This is the idea of capital as a moat.

Do you want to go and spend several years and a few billion quid buying a forest, building water slides, and then hoping people show up?

And even if you did want to do that, could you convince enough people to give you the money? How would that investor meeting go?

It’s not exactly the most compelling pitch.

That makes Center Parcs an incredibly defensible brand. They have a cornered resource that would take billions to replicate, which is why they have such strong pricing power — and take full advantage of it.

That debt though

So there’s a lot of capex, and with it, a lot of depreciation. What about the interest?

Well, Center Parcs has been carrying debt of anywhere from £1.8bn to over £2bn for the last few years, paying around £100m per year just in interest costs, at rates of 5-6%.

That seems like an awful lot. At £500m of revenue, that means around 20% of revenue goes straight towards servicing that debt.

But, crucially, Center Parcs has the cashflow to cover it. Remember, they’re making 75% gross margins: because the accommodation has almost no cost of sales attached to it, outside of cleaning and maintaining the lodges. They own these assets outright — they just borrowed a bunch of money to buy them.

So in fact, this interest is essentially the COGS for the accommodation business.

It’s no different to taking out a mortgage, buying a single family home, and renting it out. It’s just on a bigger scale, with added whirlpools.

So we could restate the P&L like this, with a new measure we’ll call EBDAT:

Which means that even with this debt servicing, Center Parcs produces a decent amount of EBDAT that they can invest in maintaining and upgrading their sites.

Given the asset-heavy nature of this business, the cashflow statement is where we see all this action in detail. Let’s take a look.

This is for FY 2022. As it turns out, the EBITDA of £245.6m is a good proxy for the cash generated from operations, which was £276.6m.

Center Parcs took that £276m of cash, re-invested £46m back into business in capex, and paid £100m of debt service.

There’s also a big movement of £70m in there, which is repaying a working capital loan to Brookfield, which they presumably needed during Covid.

So on a normalised basis, Center Parcs generates around £130m per year in free cash flow.

That means EBITDA of £245.6m isn’t a good measure of profitability. Neither is the net profit of £66.2m. The real number is somewhere in between those two, and it takes some digging to get to a reasonable answer.

So how much is Center Parcs worth? That’s where we’ll make our final stop today.

Is Center Parcs worth £5bn?

At very rough numbers, if Brookfield bought Center Parcs for £2.4bn, and have averaged a debt load of around £1.9bn over the last five years, that implies they brought around £500m of their own money to the party. These numbers won’t be perfectly correct, but they’ll be close enough.

And in fact these numbers match what was reported in the Financial Times. Brookfield acquired Center Parcs for £2.4bn in 2015, and the sale is expected to include assumption of the existing debt of around £2bn.

Importantly, the FT claims the independent valuation of the five UK sites was around £4.1bn, based on the real estate alone.

That’s £4.1bn to buy yourself some wonderful forest land, lodges, swimming pools, bars, and restaurants. Like Richie Rich, this could be yours and yours alone:

There is, of course, also an operating business on top, generating anywhere from £20-60m in net income per year, depending on occupancy.

Given that occupancy is back up at the 98% level, it seems fair to use the pre-Covid years as a good barometer of net income going forward. Admittedly I’m cherry-picking the best years here, but let’s see where we land.

The operating business alone could be worth around £700m.

I’ve been generous and stuck a 12x multiple on earnings because it’s such a durable brand, with low competition, and big pricing power, so that feels fair to me.

You’ll want to buy both the property and the operating business, I assume? You can’t really have one without the other.6

Given the £4.1bn valuation of the property, and around £700m for the operating business, we can quickly come to an all-in valuation of around £4.8bn.

Which is bang in line with the price Brookfield are hoping to get.

The final question is: given the need for so much debt to be involved, what happens as interest rates increase?

Remember, right now Center Parcs has just under £2bn in debt, and is spending around £105m a year in interest cost, which implies an interest rate of around 5.4%.

Importantly, that debt is at a 3.6% premium to the UK base rate.

And, crucially:

an acquirer will need to borrow another £2bn

UK base rates are now 4.5%, and still likely to climb.

Let’s say the buyer agrees on my £4.8bn valuation. They’re also bringing 20% equity to the table.

That means the buyer will need to find an additional £1.9bn from somewhere — and take out new debt, at significantly higher interest rates.

So at an acquisition price of £4.8bn, the buyer will need to come up with an extra £155.1m per year, just to service the debt.

And looking at the 2022 cashflow, it’s not there.

There’s no margin for error here, and I certainly wouldn’t lend someone £1.9bn to get after it, unless I had some mega-covenants in there.

Which means that for a £4.8bn acquisition to make economic sense, the buyer has to do one, several, or all of the following:

find cheaper debt

bring more equity to the table

increase operating cash flow

decrease capex reinvestment

This does not bode well for the price of a 4 bedroom lodge exclusive lodge.

That said, the cashflow figures above are based on 2022 results, and the performance in 2023 so far looks significantly stronger. It’s possible that going forward, this deal still works.

Right now, an army of analysts around the world are doing exactly what I’m doing, and building their own forecast model to figure out how to make this deal pencil. They’re likely figuring out where the cheap debt is, how much they can increase room rates, and calculating the price elasticity of a leathery rump steak.

So is Center Parcs worth £5bn?

No idea. I guess we’ll find out if and when a deal closes.

Sorry. Not the most satisfying answer, is it? Life’s like that sometimes.

Carveouts

I have barely anything to recommend this week, because writing this post has consumed so many free hours. I am re-reading Will Thorndike’s fantastic book The Outsiders, a study on several unconventional CEOs, and the capital allocation decisions they made. If you like this sort of post, you’ll love the book.

Speak soon.

Andrew

translation: pints of beer

Source: Financial Times ($)

This is also where firms like Permanent Equity differentiate, by having a fund that’s either open-ended or with a very long life. It means if they have high-quality assets, they can just hold for the long-term, rather than needing to sell to return capital to investors.

The idea of ‘EBITDA’ was coined in the 1970s by a wonderful CEO named John Malone, who was at TCI. The idea is that it’s as close as possible to representing the operating cash flow of the business, which you can then reinvest, pay off debt, acquire other companies, repurchase shares, or distribute to shareholders. For more, check out the book Cable Cowboy.

This isn’t strictly true actually: you could buy the operating company and just lease the property from someone else, although you’d be making yourself completely beholden to that person. More on this next week.

Great read. Am off to Center Parcs next month. Will brace myself!

100% equity-funded business would have a higher cost of capital than one partially funded by debt...