The niche software company going toe to toe with Adobe

And some classic investment analysis techniques

Hello to the 165 new subscribers this week, bringing our motley crew up to 1,929 balance sheet groupies for this week’s Net Income. I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO and writer here in the UK

Two things this week:

Yes, you’re receiving this on a Sunday, not a Thursday — you have not time-travelled, life just got in the way. C’est la vie.

We now have a shiny new domain name, NetIncome.co, where you can head to for all of the archive.

As always: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

If there’s one thing that Warren Buffett and I have in common, it’s our love of cheeseburgers.

But if there are two things that Warren and I have in common, the second is that we both rue our mistakes of omission. We regret the mistakes from actions not taken.

Warren, for example, kicks himself for not investing in companies he fully understood and knew to be a great investment at the time: Disney, Walmart, Fannie Mae, to name but a few.

And me? In 2011 I interviewed at a large institutional investment company, and as part of the interview process, they asked me to recommend some investments.

My two recommendations were:

Google

Apple

I gave a good justification for why: both dominant in their respective markets, both producing high-quality revenue, both benefiting from growing smartphone adoption. The interviewers agreed, although not enough to give me the job.

I promptly went away and did… nothing.

In my defence, from its IPO date to the day I recommended that investment, Google stock was up 5x in seven years, and the market cap was $166bn on $8.5bn of net income, a P/E ratio of 19.5. It looked a bit frothy to me.

Since then, Google stock is up 9.2x in 12 years, a 20.3% annual return. (I don’t want to know the numbers for Apple.)

In 2011 Google did $38bn of revenue, and $8.5bn of net income, so a net margin of 22%.

In 2022, Google (rebranded, for some reason, as Alphabet) did $280bn of revenue, generating $60bn of net income — still 21% net margins, even at that scale.

That’s despite funding all manner of speculative R&D projects, poorly executed product launches, and much more (does anyone know what Google Hangouts is called these days?).

They can generate a spectacular amount of cash because software is the best business model of all time.

It’s a model built on a mountain of leverage, as defined by the angel-investor-turned philosopher Naval Ravikant.

With zero marginal cost of replication, you can build something once — like a great search engine with real-time ad auctions built in, or a petroleum-industry vertical market software product — and serve it up to your customer again and again at virtually zero incremental cost. Serving one customer costs practically the same as serving thousands of customers.

(and if you don’t have the ability to make software, you can do something with equal amounts build-once-sell-many-times leverage, like, y’know, a newsletter)

Today’s company is not at the same scale as Google — because very few companies are — but is a phenomenal example of software leverage even at a small scale.

This is the Serif Group:

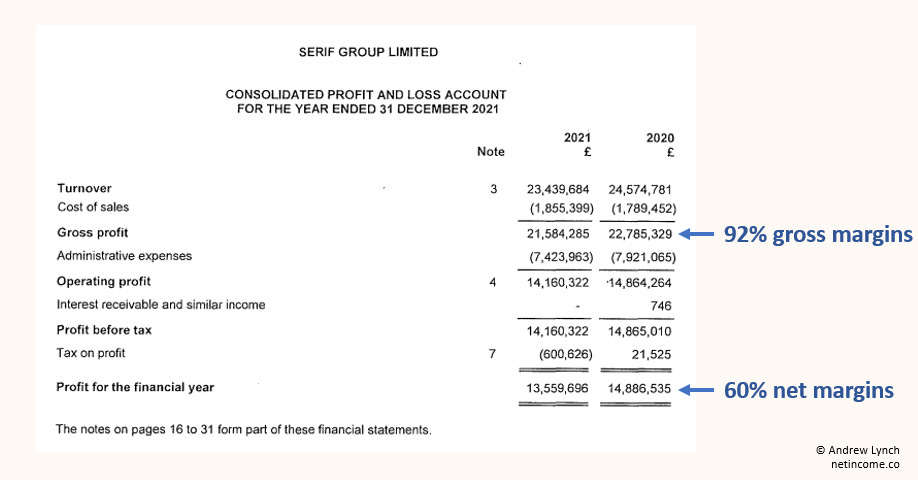

This is a niche software company in my home city of Nottingham, UK, and they are generating £14m of net income per year, on revenue of around £24m per year, giving them net margins of around 60%.

What are they selling? How did they get here? And why do they pay so little in tax? All this and more in today’s newsletter.

This week’s Net Income is brought to you by NextScout. NextScout connects executives with highly skilled overseas talent, talent that costs 75% less than a US or UK equivalent.

Unlike other recruitment services, you only pay NextScout when you hire a remote worker who meets your standards — which, thanks to their rigorous candidate selection process, is a near-certainty.

Not sure what tasks to delegate? NextScout have put together this guide to help you get started.

So if you want to reduce your labour cost, NextScout can help. Just fill out this short form, and they’ll take care of the rest.

Who are the Serif Group?

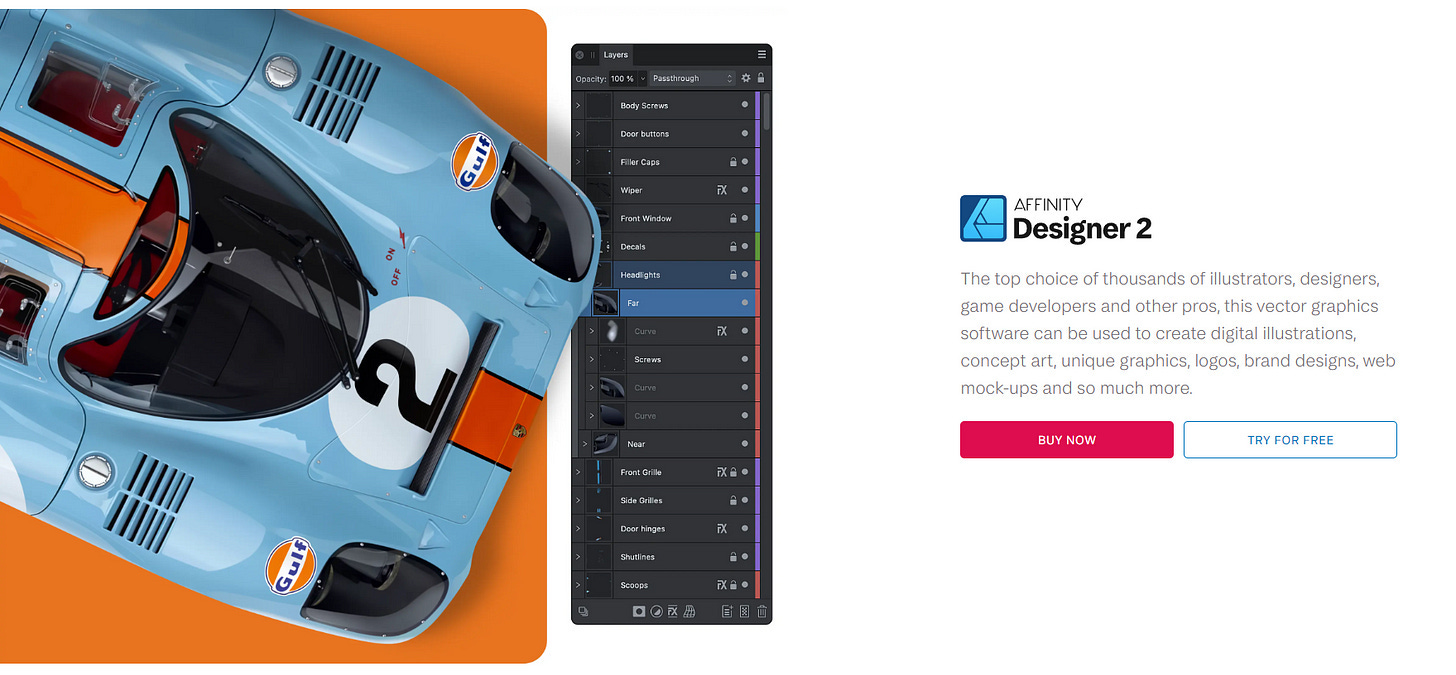

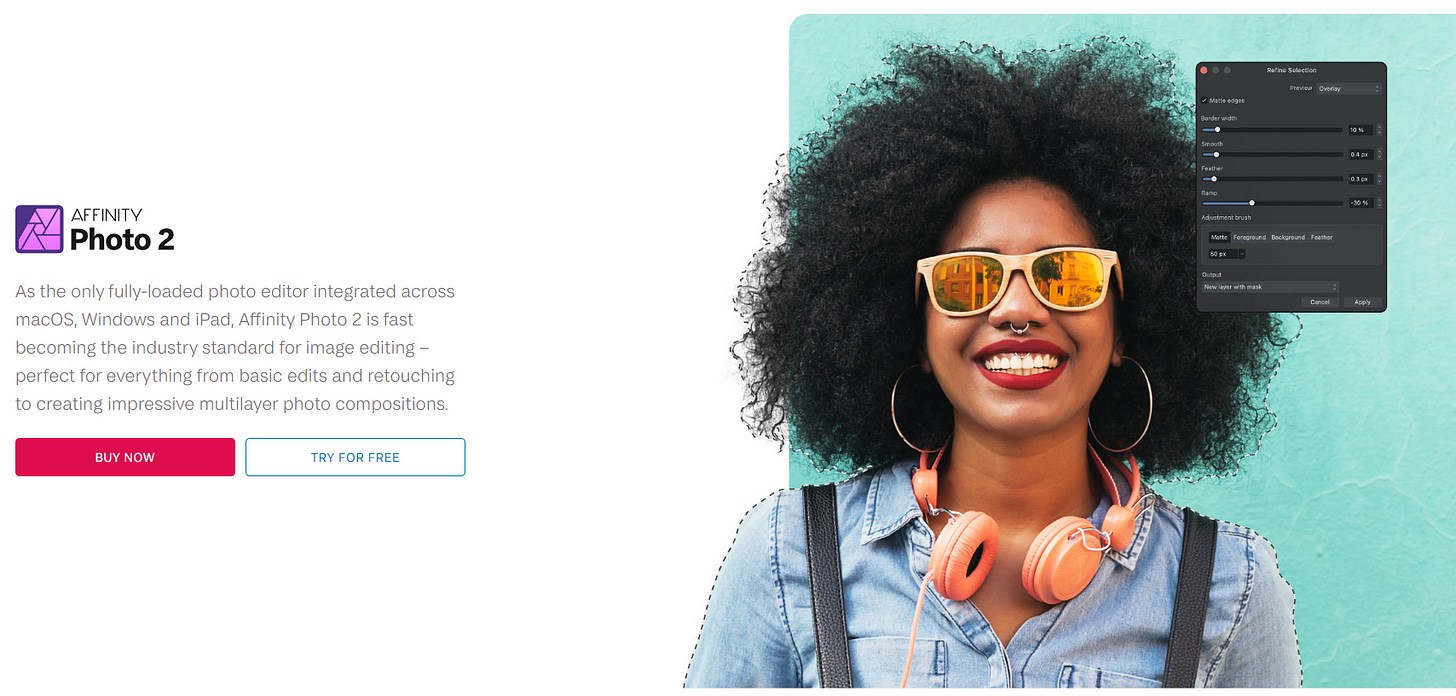

Founded in 1987, Serif Group to day is the publisher of three core apps across Windows, macOS and iOS:

1) Affinity Designer

2) Affinity Photo

and 3) Affinity Publisher

In other words, they’re a direct competitor to Adobe’s creative cloud suite of Photoshop and InDesign.

You’d think that taking on one of the biggest and best-known software companies in the world would make things difficult.

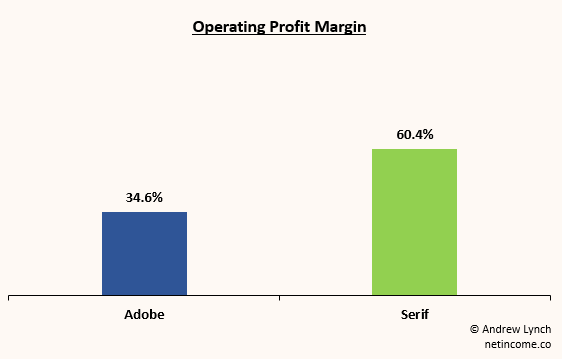

But while Adobe does have significantly higher revenue per employee:

...Serif actually has better operating margins than Adobe, albeit on a fraction of the revenue:

And still — who cares if you’re not the size of Adobe when your shareholders are getting rich? They’ve paid out £26m in dividends in the last two years:

So the Serif shareholders aren’t “private jet” rich, but having driven past their offices, they’re certainly “Porsche with private number plate” rich, and we all know that basically everything after that is just vanity money.

There are some key lessons to learn from the Serif story, which I’ll share next week. First, though, they’re a great excuse to do some investment analysis and break out the XIRR formula and some discount factor tables.

Let’s analyse an investment!

Serif started out as a software and hardware reseller. Founded in 1987, its early filings contain wonderful passages like this a glimpse into what the tech industry used to be like — celebrating the widespread adoption, at last, of GUIs as a way of doing business:

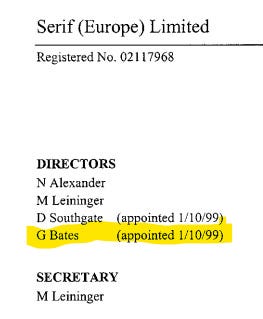

Capitalising on these industry shifts, Serif grew steadily throughout the 1990s, selling a combination of hardware and software to UK businesses, until 1999, when a chap by the name of Gary Bates was appointed to the Board of directors:

At this point the company was doing about around £6-10m per year in revenue, with some good years, some bad years.

By early 2004, the company had grown top-line revenue significantly, but that wasn’t translating into bottom-line profits:

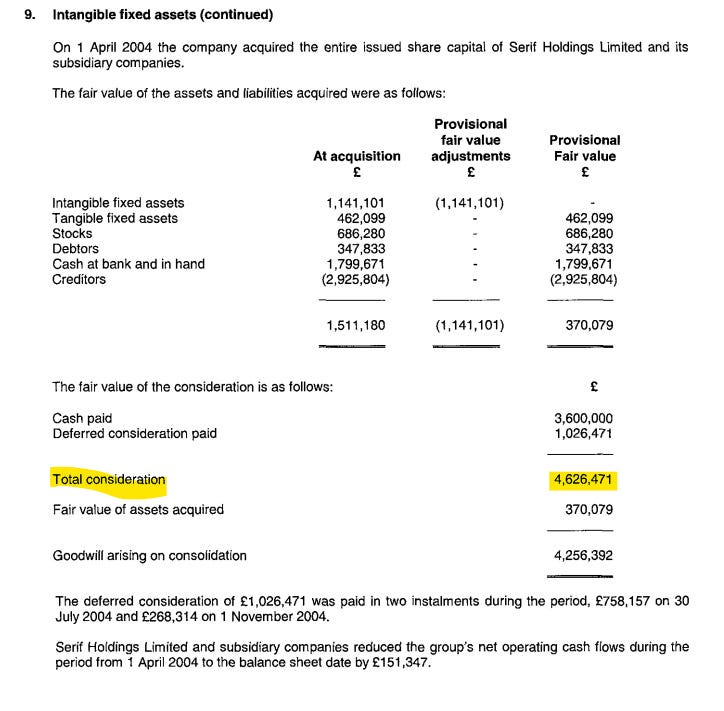

So, sensing an opportunity, Gary Bates and his business partner James Bryce took a bold swing, and bought the company in a management buy-out, for £4.6m:

Now, £4.6m seems punchy when the total net income of the company over the prior three years was only £1.4m. In fact, I went through the filings and calculated the EBITDA for the 2001-2003 period:

Average EBITDA over this period was £827k, meaning that on a total purchase price of £4.6m, they paid a 5.6x EBITDA multiple to acquire a fairly middling business:

One important point to note here is that the acquisition was funded by £2.3m of equity, and £2.25m of loans:

Which I appreciate doesn’t quite add up to £4.6m — my guess is the balance came from the deferred consideration in the purchase price, meaning they could run the business for 6 months or so and generate enough cash to then pay off the last bit of the acquisition price.

So putting in ‘just’ £2.3m of their own money in 2004, Gary and James acquired Serif Group, and all of its software, IP, and operations, which up to that point were mildly profitable at best.

Was that a good investment?

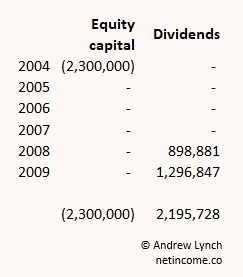

Hindsight is wonderfully 20/20, so we can look at the dividends paid out since that 2004 acquisition to see what returns they’ve generated.

I’m not assuming any terminal value of the business, and I’m only counting dividends paid to shareholders as cash out. Neither of those are entirely true, but it allows us to calculate the IRR, the Internal Rate of Return on the acquisition:

A 27.4% internal rate of return over 17 years..

Not bad at all. And they still own the business.

Serif today has averaged around £14m per year in EBITDA, so assuming the EBITDA multiple stays constant at 5.6x, I estimate the business is worth £76.5m today.

And realistically, that multiple is a lot higher now than it was then -- it’s a much bigger, more profitable, more resilient business, all of which would drive the multiple up.

If we wanted to pull out another investment analysis technique, we can use a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model.

Again, we have perfect information here so it’s cheating a little, and again, I’m simply using equity capital out and dividends back in as the cash flows, but let’s see how it shakes out using an 8% discount rate. Let’s also throw in an assumption that they sold the business for that estimated £76.5m valuation (ignoring taxes) at the end of 2022 as well.

By acquiring Serif Group in 2004, Gary and James generated £37m of value for themselves. What a great decision.

By the way, to get the discount factors for this, I just googled “discount factor table” -- these values essentially tell you what your £1 today is worth in the future at different interest rates. The higher the interest rate, the lower the discount factor, because in periods of higher interest rates, you should value money now more than money in the future.

‘Risk-free’ investing?

The one thing I want to point out today is not that these two guys made a phenomenal investment -- which they did -- but that they made a smart investment, one in which there was asymmetric upside.

It’s a great example of what investor Mohnish Pabrai calls a Dhandho investment.

Dhandho (pronounced dhun-doe) is a Gujarati word. Dhan comes from the Sanskrit root word Dhana meaning wealth. Dhan-dho, literally translated, means “endeavors that create wealth.”

Pabrai, Mohnish. The Dhandho Investor

Dhandho investing, as practised by Pabrai and others, is all about finding these ‘heads I win, tails I don’t lose too much’ scenarios.

That’s exactly what Gary Bates and James Bryce did when they acquired Serif in 2004. Here’s why.

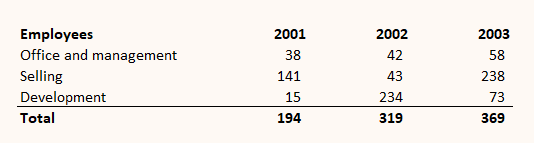

On the face of it, splashing out £4.6m for a company that is at best mildly profitable seems foolish. But: remember the company had made pretty good money in 2001, but not much at all in 2002-03. That’s because they’d hugely increased headcount:

So Gary and James probably thought that in the worst-case scenario, they could run the Elon Musk playbook (decades ahead of Elon), lay off a bunch of people, get the company back to a reasonable level of profitability, and get their money back — or most of it, at least — in a few years.

Best-case scenario? They could invest in new products, hit upon one, and become very wealthy men.

Heads I win, tails I don’t lose too much. Classic Dhandho investing.

In reality, by 2009 Serif had paid out enough in dividends that they’d essentially got back to breakeven on their initial investment:

Which meant everything after that was a freeroll, playing with house money. They could afford to take some swings. And swing they did, and it certainly paid off for them.

We’l leave it there for today — more to tell in this story next week, in particular:

how Serif completely transformed its business model;

and why they’ve only paid a total of £2.2m in tax on £64m of pre-tax profit over the last twenty years.

Carve outs:

Sophie, aka @netcapgirl on Twitter, had this incredible exchange with Elon Musk:

which she then expanded into this incredible analysis of Twitter’s LBO so far, and where they could go from here. Highly recommend it:

Speak soon,

Andrew