Not all EBIDTA is created equally

TCI, Serif, and why tax policy is sometimes wonderful

Hello! Welcome to the 603 new readers since last time out, joining our community of 2,532 business nerds.

As a reminder – it’s been a few weeks! — I’m Andrew Lynch, a small business CFO here in the UK. I love finding great companies and sharing their stories, and the lessons you can apply in your own company.

One favour to ask: if you like this, please share it with a friend.

Last time out we looked at the Serif Group, a wonderfully profitable niche software company, based in my home city of Nottingham, UK.

With zero outside funding and a small team of around 75 employees, they’ve managed to create a David of a software company that competes directly with the Goliath of creative tools, Adobe. It lets you create great art, like this:

Putting aside for a second the question of whether AI will completely destroy this industry, today Serif’s P&L looks like this:

<obama_notbad.gif>

And more importantly, their cash flow statement looks like this:

There is not a sweeter sight in the world than a company that has made £28m in operating cash flow in two years, and paid out basically all of it as dividends.

Because if there’s one thing that gets a CFO’s heart racing, it’s what my friend Secret CFO calls Maintainable Free Cash Flow, or MFCF.

Let’s do a quick primer for everyone out there and define some terms.

Profit is an accounting definition – when we’re talking about, say, net profit, we’re talking about total revenue, less all expenses, over a period of time.

Crucially, though, that profit figure could include a few important assumptions, like:

Depreciation charges

Amortisation charges

Accrued costs or income

Adjustments for prepaid revenue or expenses

which is why, in their books Financial Intelligence for Entrepreneurs, the authors stress repeatedly that “profit is an estimate.”

Say it again. Profit is an estimate.

Profit is always an estimate, because the poor accountant preparing that profit figure never has perfect information. We can never know exactly the value of our fixed assets at any given time, so we use depreciation schedules to approximate it. We can never know exactly what this month’s energy bill will be until two weeks after the month-end close, so we accrue an estimate. And so on, and so on.

On the other hand, cash flow is known and knowable.

In a company’s financial statements, the cash flow literally represents the change in bank balance from the start of the year to the end of the year. If on Jan 1 your bank balance is £100,000, and on Dec 31 your bank balance is £200,000, then your cash flow for the year was £100,000, and no amount of accounting shenanigans can say otherwise.1

So where does EBITDA come in?

EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortization. I enjoy standing on the shoulders of giants, so here’s a nice diagram from Secret CFO to show where EBITDA sits on the P&L:

The idea of EBITDA was created by the CEO of TCI, John Malone, back in the 1980s.

Malone was an incredible entrepreneur, whose journey is chronicled in the wonderful book Cable Cowboy. In the early 1970s, Malone saw that the cable industry:

was growing rapidly rapidly growing;

was fragmented across many providers; and

had incredibly sticky customers willing to pay a lot for the service.

That led to Malone’s bold strategy: borrow lots of money to buy lots of cable franchises across the US, ensuring that the cash flow from each acquisition could cover the debt repayments on that asset. Over time, the debt would get paid down, the asset value would grow, and TCI’s shareholders – including Malone – would get very rich.

It’s a beautiful strategy. And it worked like a charm.

This strategy had one big downside though.

Acquiring cable franchises – and spending money on upgrading them – leads to big costs in your P&L for depreciation and amortization.

How did Malone deal with that?

A brief sidebar on non-cash charges

Depreciation and amortization are examples of non-cash charges in accounting. But what exactly are they?

Depreciation is the cost charge that goes in your P&L when your physical assets go down in value.

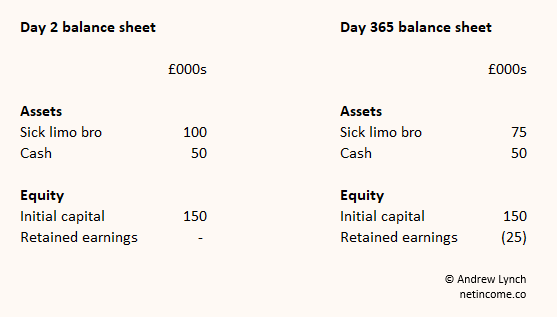

The canonical example is a car. Let’s say you’ve invested £150k to start a private limo rental business. Your first step is to go and buy a brand-new limo for £100k exactly.

When you buy that limo, you’re exchanging one asset – cash – for another asset – a car. Here’s how that shows up on your balance sheet:

The moment you drive it out of the limo dealership, assuming that’s a real thing, the car loses some value. That loss of value is the depreciation.

In this unfortunate example scenario, your fateful investment decision was on 1st March 2020, and thanks to Covid and your distinct lack of sales ability, you managed to go the whole year without ever making a single limo rental. Your limo, however, still lost a big chunk of its value. 25% of its value, in fact.

Technically you’ve lost £25k. But your cash balance has stayed the same. The loss is due to the drop in the value of your asset. That’s a non-cash expense – but it’s still a real expense, because if you tried to sell that limo, you’d get less for it than what you paid.

Depreciation applies to physical assets. Amortization is exactly the same principle, but applied to intangible assets. Things like patents, licences, IP, trademarks, that sort of thing.

Let’s take your struggling limo rental company again. What if, in order to drum up business, you bribed a city official £20k to give you exclusive limo-operating rights for the next five years?

If you managed to stay out of jail, then that exclusive operating licence is an intangible asset with a life of five years – so the correct accounting treatment is to expense £4k per year to the P&L, slowly reducing the value of that intangible asset over its five year useful life (and of course, if the city official ever goes to jail, write it down to zero).

Importantly, even though depreciation and amortization are non-cash charges, they are still tax-deductible.

Got it? Good. OK, back to the TCI story.

Malone’s wonderful strategy

Chronicled in the wonderful book Cable Cowboy[link], Malone’s strategy was to borrow lots of money, and buy tons of cable franchises. Over time, the value of those franchises would go up. Those acquisitions also led to big interest charges (from the debt used in the acquisition), as well as large depreciation and amortization charges, all of which reduced TCI’s reported earnings, and therefore their tax bill.

Here’s a visual of the strategy:

In fact, such was Malone’s insistence on this strategy that he famously said to investors:

“If you’re going to ask about quarterly earnings, you’re at the wrong meeting, and you probably own the wrong stock. What we care about is value. We want to create value for our shareholders… There is a big difference between creating wealth and reporting income.”

And Malone threatened to fire the accountants if TCI ever reported a profit.

(NB please don’t do this, we need jobs now before AI takes them all, ty)

The downside of never reporting a profit is that investors back in those days – unlike the ZIRP-crazed investors we’ve seen in the last 15 years – liked to see a company actually making a profit. Will Thorndike talks about this in The Outsiders:

Malone [realized] that maximizing [reported] earnings… the holy grail for most public companies at that time, was inconsistent with the pursuit of scale in the nascent cable television industry. To Malone, higher net income meant higher taxes, and he believed that the best strategy for a cable company was to use all available tools to minimize reported earnings and taxes, and fund internal growth and acquisitions with cash flow…

While this strategy now seems obvious… at the time, Wall Street did not know what to make of it. In lieu of earnings… Malone emphasized cash flow to lenders and investors, and in the process, invented a new vocabulary, one that today’s managers and investors take for granted. Terms and concepts such as EBITDA were first introduced into the business lexicon by Malone.

He invented EBITDA as a metric to give Wall Street something to focus on instead. It’s a proxy for operating cash flow.

Investors loved it. TCI got the funding it needed, and Malone repaid that investor trust was a wonderful success, returning on average more than 30% per year for 20 years, until Malone sold the business to AT&T in 1999 for around $50bn. Not bad at all. And as Thorndike points out, he created the concept of EBITDA, which these days we take for granted.

But importantly, not all EBITDA is created equally. Malone used depreciation and amortization to reduce TCI’s tax bill, sheltering their earnings from the IRS. That’s good EBITDA. But you can imagine a

Depending on the characteristics of the company, £10m in EBITDA could result in lots of cash flow, no cash flow, or many things in between.

But what if you could cut out the middle step? What if you could just… pay less in taxes?

Which finally brings us back, for the last time, to Serif.

Sometimes tax policy is amazing

Let’s look again at Serif’s P&L.

Out of £14.2m of pre-tax profit, their net profit was £13.6m. They paid just £600k in taxes – 4.2% of their pre-tax profit, at a time when UK corporation tax is supposed to be 19%. How on earth did they do that?

Two things:

1. R&D tax credits

Thanks to a wonderful bit of tax policy, if you go to the UK government and say, “I spent £1m on researching and developing new technology with an uncertain outcome,” they’ll say, “jolly good! Here’s £300k back. Thanks for doing your bit to support innovation.” It’s there to incentivise innovation and risk-taking, which it generally does.

That said, it’s a slightly grey area, which has unsurprisingly led to an army of grifters and consultants telling you they can get you tax credits for basically anything – for a fee. Sadly, I’m yet to find a consultant who can get me tax credits for a business-themed email newsletter. If you’re out there, please email me.

2. Reduced taxes on profits from patents

If you’ve been reading Net Income for a while, you might remember the patent box from our post on Petex, another UK-based software company.

The ‘Patent Box’ – so-called because it’s literally a box on your tax return that you fill in – means that you only pay a rate of 10% corporation tax on any profits generated from patented IP.

Let’s turn to the notes in Serif’s accounts:

At usual rates, they would have paid £2.69m in tax. But thanks to £978k of R&D tax credits, and £1.2m of patent box deduction, that £2.69m of tax becomes just £600k.

In fact, we can do some quick maths here:

Serif is generating 94% of its pre-tax profit from patented IP – saving them a fortune in taxes.

This is why not all EBITDA is the same.

All else being equal, you’d pay a higher EBITDA multiple for Serif than any other business.

Not because of any market dynamics, or unique customer relationships, or reputation in the market.

But because you get to keep more of the profits.

No marginal cost of goods sold. Infinitely replicable product, anywhere in the world. And tax policy actively encourages this sort of risk-taking. Software really is the best business model of all time.

And this is why Serif was such an amazing acquisition.

Buy a business that’s generating residual cash flow from a legacy business.

Re-invest significant portions of that into new software products, which generates significant tax credits in the process.

If you create a great product, patent it and sell it and make loads.

If you don’t, well, just enjoy the residual cash flow from the thing you bought.

Heads I win, tails I don’t lose too much. A phenomenal value investment.

Next time out we’ll look at another tech acquisition that was even better. In fact, our next analysis is on what’s probably the most profitable technology company in the UK. Keep an eye out for it in your inbox soon.

Carve outs

I finally got round to reading The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership. I’m about 30% of the way in right now and it’s possible this will be a transformational book for me. More to come on this.

I read that book because Levels CEO Sam Corcos recommended it on this podcast with Tim Ferriss. If you’re into business ops, efficiency and productivity, deep work, all that sort of stuff, you’ll love this interview.

If you want more about Levels, this piece in the Generalist is well worth a read. The title, ‘A Cultural Anomaly’, hints at why they’re interesting. The piece opens: “There is not a company on earth that runs quite like Levels.”

Lastly, I’m starting a new professional opportunity shortly as Head of FP&A for Blue Light Card, an amazing rocket ship of a business here in the UK. They have an incredible mission, and are assembling a top-tier team too. I can’t wait to get started — but fear not, Net Income will continue.

Lastly, I’m super-interested in what tech firms are using as their finance stack, so I’m doing some research and collating it all in one place. Here’s what I’ve got so far:

Thanks! Speak soon.

Andrew

This is also why one of the first things that auditors ask for in a financial audit is your bank statements. You can put an awful lot of nonsense through the P&L, but unless you’re photoshopping your bank statements – which isn’t unheard of – then the bank statements are the ultimate truth.

Such a great piece

Man, I don't know how but I never realized you're running a newsletter.

This breakdown was great to read, and easy to understand, even for a "big picture" guy like myself who doesn't really have the "accountant" eye.

Fixed my mistake and subscribed!